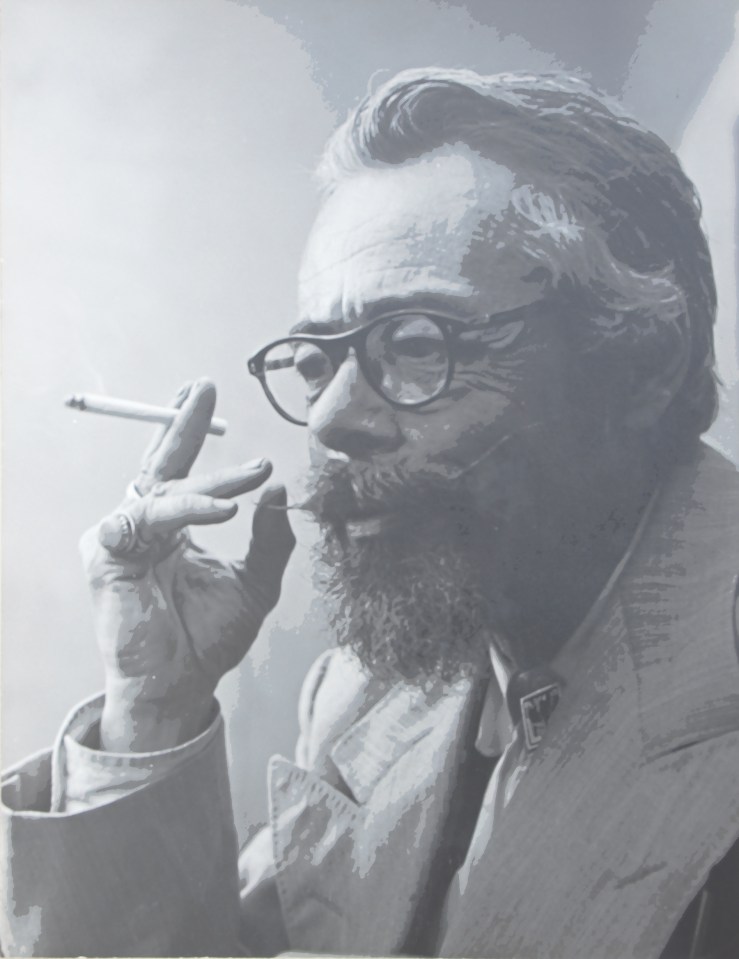

Special announcement: We’ve officially extended our MORANG AND FRIENDS exhibition through Friday, January 2nd. Come trace the legacy of ‘Santa Fe’s Toulouse-Lautrec’!

Cheryl Ingram strolls into Matthews Gallery and beams up at a sign that hangs high on the wall. “There it is, Claude’s Bar,” she says. Ingram is the co-owner of Silver Sun Gallery, which is just down the street from us. Her gallery once housed Claude’s Bar, and this Santa Fe relic is usually on display there. Ingram kindly lent it to us for our MORANG AND FRIENDS exhibition. Though Claude’s was established just two years before Alfred Morang’s death, he quickly took a liking to the tavern and its charismatic owner, Claude James. In fact, Claude’s was his last stop before the fire that ended his life in January, 1958.

About two decades after Morang’s death, Ingram and her business partner Deanna Olson arrived in Santa Fe. They were retired school teachers who had been traveling around the country selling handmade Native American jewelry. When they reached the City Different, they stuck around and founded Silver Sun. In the years since 1980 when they opened the business, they’ve become the keepers of countless stories about the infamous saloon that preceded them. As Ingram strolls around the gallery smiling at the colorful canvases, she can’t help but pass on some fascinating tales of Canyon Road.

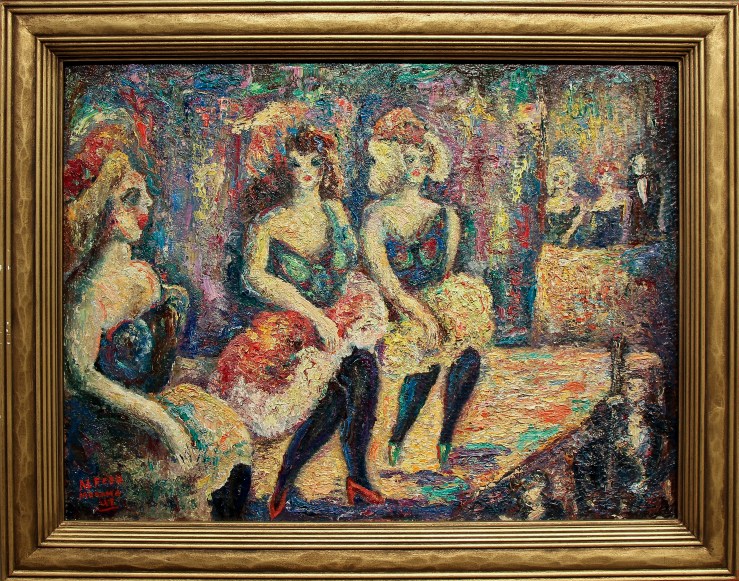

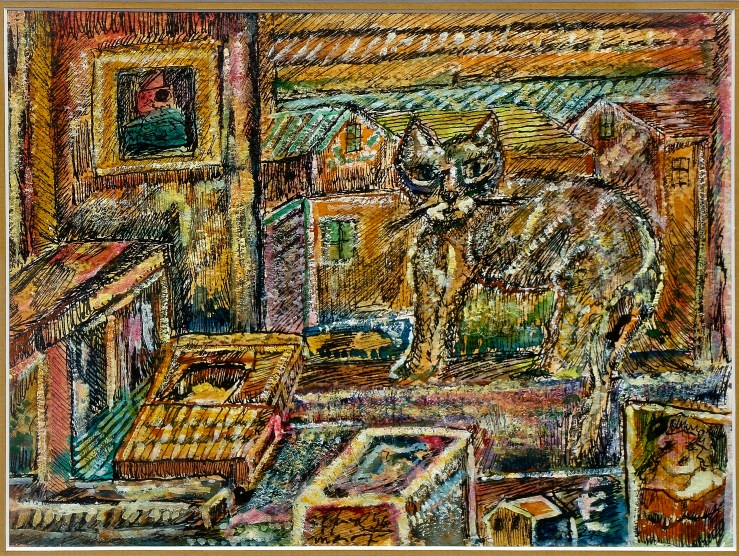

Ingram analyzes a painting of ladies dancing on a stage, concluding that it’s probably a view of El Farol. She and Lawrence linger by a watercolor of a bustling restaurant and try to identify where it might have been. She finally stops before a large painting titled ‘The Women at Claude’s’, and the stories really start rolling.

“Claude’s mother was French, and she married an editor at the New York Times whose last name was James,” Ingram says. In the 1950’s, Claude and her mother embarked on a road trip to California along Route 66. On their way back they took a detour to Santa Fe and never left.

Claude followed in her father’s footsteps and took a job as a journalist for the Santa Fe New Mexican. One year her house caught fire, killing her two corgis. A reporter snapped a photo of the dead dogs and published it in the paper the next day. Claude was so disturbed that she swore off journalism. She and her mother bought a building on Canyon Road’s 600 block and opened a bar and restaurant.

At first it was a fancy establishment where Claude’s mother hosted intellectuals from Paris, but later it was better known for midnight parties and wild bar brawls. “The Santa Fe police were always hoping it would burn down,” Ingram says. “Whenever they got a call about it, they were disappointed that there hadn’t been a fire.”

Alfred Morang, The Women at Claude’s, Oil on Canvas

Alfred Morang, The Women at Claude’s, Oil on Canvas

Ingram stares intently at ‘The Women at Claude’s’ and warm recognition spreads across her face. “Claude had dark hair, and she was short and squat like the woman in the center of the painting,” she says. In fact, with a little more analysis, Ingram concludes that the woman probably is Claude. “She’s standing behind the bar, so it very well may be Claude serving the clientele. That would be her lover behind her.”

Claude often tended bar barefoot with a pack of cigarettes folded into the sleeve of her shirt, Ingram says. She would throw patrons out of the bar “by the belt and shoulder” if they got too rowdy. “Canyon Road wasn’t paved then, so the landing was a little softer, but you didn’t mess with Claude,” Ingram says with a laugh.

As she continues, we flip our tape recorder on:

She was a handsome woman, but not a pretty woman. She was short but you didn’t mess with her.

A guy came into Silver Sun about 1982, looking for Claude’s Bar. I told him he was a little late, and he told me a story about Claude.

He said he had ordered a beer and Claude was working the bar. He noticed this pretty woman sitting at the other end of the bar. He tried to hit on her, and next thing he knew, his tie, shirt and coat were pulled across the bar. “You leave my woman alone,” Claude said. He was so upset, he didn’t finish the beer and left.

Each corner of the bar had its own persuasion. You had the gay men over here, the gay women over here, and the three piece suits were over there with the ladies of the night. Claude was like a teacher in the classroom: one corner did not mess with any of the other corners, or your fanny was out of there.

There was an ambiance that was going on in there that was truly Santa Fe of the period, and that’s why she was so popular. You were okay if you got in there. Even if you got stumbling drunk, someone would be there to protect you from some nasty politician or a cowboy with a gun.

There were honest-to-god cowboys who wore guns. A fight broke out between them and the gay guys once, and everyone had guns. There were two lines of guns, about ten or twelve feet apart, and they were drunk and shouting. That story came from a lady who was hiding under the bar. She was the barkeep on Saturday night. It looked like they were shooting around each other, trying to scare each other. One guy did take a hit in the fanny, however. When the cops got there, they just took the whole batch. The next day, the barkeep quit.

Towards about 1970 or 1971, there was a dance floor way in the back where a sculpture garden is now. A guy named Jimmy was up there playing—his wife told me this story—and looked past all the drunks to the door. Here was this lanky guy with a guitar case who saunters over to Jimmy. “Mind if I play along?” he says. Jimmy just had a cow. They played all the rest of the night together, and no one besides Jimmy recognized him. It was Jimi Hendrix. They were all too drunk.

Claude eventually lost interest in bar tending and hired someone else to manage the establishment. The saloon closed in the late 1970’s but its charismatic owner remains a legend among Santa Feans. It’s fascinating to hear Ingram’s tales, especially because they’re rare firsthand accounts. They’re all from people who have passed through Silver Sun over the years to pay tribute to Claude’s.

Since MORANG AND FRIENDS opened two weeks ago, we’ve had visits from many people with Santa Fe stories like these. We’d like to thank everyone who shared with us. Your words have helped inspire our upcoming exhibition schedule, which will delve into many corners of the Santa Fe art colony. Stay tuned!

For more gallery news, make sure to connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.