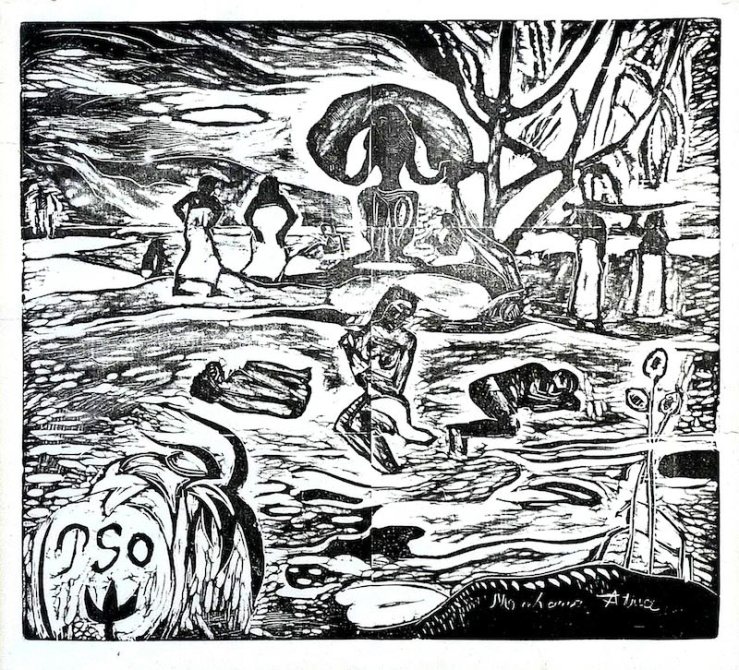

Paul Gauguin, The Day of God (Mahana No Atua), woodcut

There’s no record of what Paul Gauguin’s last lover Marie-Rose Vaeoho thought of him, but their courtship must have been rough. By the time Gauguin reached the Marquesan island of Hiva Oa in 1901, he had eczema, syphilis, malaria, tooth rot, a heart condition and a very bad liver. Local teen Marie-Rose gave birth to his daughter in September of 1902, and he died on May 8, 1903. Gauguin’s body was already rotting in the tropical heat during the burial.

This distasteful finale is an ill-fitting epilogue to Noa Noa, Gauguin’s fanciful (and mostly false) account of his early travels in Polynesia. The artist’s twilight years may have been ruled by destruction and decay, but he clung to themes of rebirth, transformation, divinity and utopia in his art and writing. The New York MoMA’s new exhibition Gauguin: Metamorphoses centers on woodblock prints and other works on paper that he produced between 1889 and the time of his death. At Matthews Gallery we have two Gauguin woodblock prints from the same period that he made to accompany his Noa Noa memoir.

From MoMA:

These remarkable works on paper reflect Gauguin’s experiments with a range of mediums, [including] radically “primitive” woodcuts that extend from the sculptural gouging of his carved wood reliefs […]. Gauguin’s creative process often involved repeating and recombining key motifs from one image to another, allowing them to evolve and metamorphose over time and across mediums.

For Gauguin, the printmaking process was a natural extension of this mercurial philosophy. It allowed him to mirror and tweak imagery between prints and even in different runs of the same print.

In New York, you can see several versions of Gauguin’s Noa Noa woodblock prints. In Santa Fe, come track the evolution of the series through two of our works. Here’s a peek—

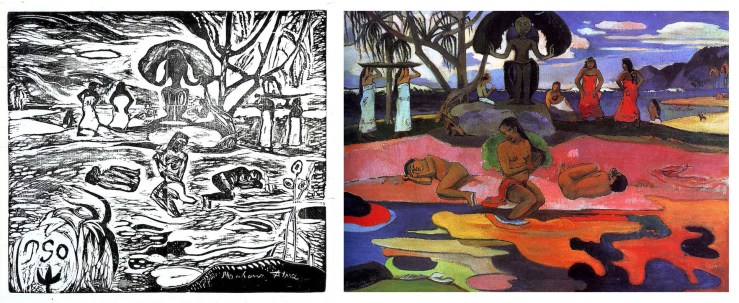

The Day of God (Mahana No Atua), our woodblock print and the painting

Our woodblock print and its oil counterpart were created around the same time and are close mirror images of each other. Both show three women on a shore with a Polynesian sculpture (based on carved Buddhist reliefs from Java) rising above them. In the painting, our eyes are drawn to the bright colors and wild abstract forms of the water. In the print, the women and the statue stand out as bold graphic elements, highlighting the symmetry of the composition.

Gauguin’s decision to reverse the composition from one work to the other brings up some interesting interpretive questions. The three women in the foreground may represent birth, life and death. If their positions can be so easily flipped, perhaps life’s course isn’t so linear either. Viewed together, the works form a loop that reflect Buddhist beliefs concerning rebirth.

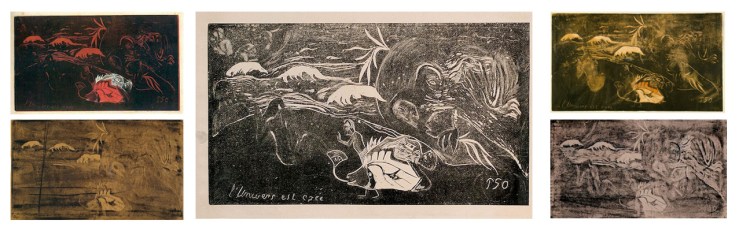

Five versions of Paul Gauguin’s L’Univers Est Cree, including ours (center)

We’ve written about our version of L’Univers Est Cree on the blog before, but Gauguin, his son Pola and artist Louis Roy made several print runs from the block. Some are crisply defined and others are murky with only a few details clearly in view. Some incorporate bright reds and yellows, while others are starkly monochrome.

When Gauguin presented his Noa Noa prints in a private studio show in Paris in 1894, he hung several versions of each print. The decision seems like the artist’s acknowledgment of his futile struggle to embrace a paradaisical version of his island experiences. As scholar Alaistar Wright puts it, the repeated, ever-changing images “allowed him to reflect on the impossibility of having any authentic experience in his dreamed-of Polynesian idyll.”

Visit us at Matthews Gallery to see Paul Gauguin’s incredible woodblock prints. To learn more, read our blog post about “L’Univers Est Cree” and listen to Lawrence’s accompanying podcast. For daily gallery news, connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr.