The very first artists who came to work in New Mexico found themselves on a harsh frontier. Harold Elderkin and his wife moved to Santa Fe in 1886 to run a gallery and teach painting lessons, but left for El Paso two years later. An artist named George Stanley tried the same thing in 1897 and failed even faster.

The 1920s saw an influx of artists who had already established their careers on the East Coast. The Southwestern landscapes they sent home would build this region’s reputation for stunning natural beauty and great art. Nowadays, Santa Fe is one of the nation’s largest art markets and New Mexico is a magnet for artists from across the globe.

Though New Mexico has changed a lot since those first creative pioneers settled here, the independent spirit of the frontier lives on through art. Our April 5-18 exhibition “State of the Art”showcases the work of seven recognized contemporary masters who work in New Mexico. Their art may be as diverse as our desert sunsets, but it’s all influenced by the Land of Enchantment.

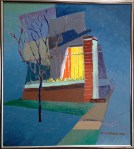

Jamie Chase moved to Santa Fe in 1980 from his home state of California. He initially found success here painting traditional landscapes, but started exploring other styles and subject matter as he developed his own visual vocabulary. His current work includes non-objective paintings, abstract landscapes and abstracted figurative paintings. “State of the Art” will feature his elegantly abstracted female figures, who roam among dazzling color fields in search of transcendence.

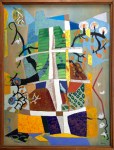

The landscape-based abstract paintings of Terry Craig are literally rooted in the earth. He uses powdered pigment, marble dust and other materials to explore the tension between careful geometric order and wild gestural strokes. The Albuquerque artist draws inspiration from colors and patterns he sees in nature, but when he puts brush to surface he surrenders to his subconscious.

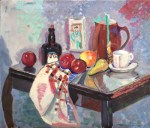

Annie O’Brien Gonzales was born and raised in Oklahoma and got her BFA in painting and art history at Oregon State University. She pursued fiber arts for many years but recently switched back to painting. You can still see traces of her fiber work in the bold patterns and colors she incorporates into her still life paintings.

“Form and line, and observation, are the tools of the passage of my self-discovery,” says 89-year-old Santa Fe artist Robert W. Hinds. The sculptor worked as an illustrator and graphic designer before deciding to explore the third dimension. His bronze sculptures are of animals and people, and often show surreal interactions between them. Hinds’ abstracted style is contemporary, but the stories he tells through his sculptures recall Classical myths.

Frank Morbillo was raised on Long Island, but moved to Montana and then Santa Fe as a young adult. His sculptures speak the same language of entropy and change as New Mexico’s majestic rock formations, with an added element of political dialogue that you’ll find in his inquisitive titles. “I often find myself walking the line between artist and activist,” he says.

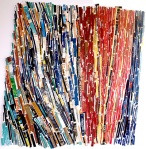

You’ll find old letters, candy wrappers, bits of string and other flotsam and jetsam in Kate Rivers‘ mixed media works. The artist, who grew up in Ohio and now lives in Santa Fe, uses these often overlooked objects to investigate memory and metaphor. Her most recent works are enormous collages made of dozens of stitched-together book bindings. Fragments of titles jumble together, encouraging new associations between the stories and characters behind them.

Diane White may be well versed in traditional still life techniques, but a closer look at her serene paintings of ceramic pots and other vessels will lead to fantastical discoveries. The Santa Fe artist, who worked for many years as a potter before studying painting at the Loveland Art Academy, weaves elements of magical realism into her works right under the viewer’s nose. Magical realism is a literary genre made famous by writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez that illustrates extraordinary events in the context of a quotidian setting. Pay attention to every detail in White’s work and you’re sure to discover something supernatural, from a leaf transforming into a butterfly to a bouquet of lilies melding with the night sky above it.

“State of the Art” opens Friday, April 5 from 5-7 pm and runs through April 18, 2013. Check out our Facebook and Twitter pages for more information.