Palace of the Governors Image Specialist Hannah Abeldeck sifts through the archives

“I think what you’re referring to is what we call ‘orphan photographs,'” said Palace of the Governors Photo Archivist Daniel Kosharek over the phone. “We have boxes and boxes of them.”

We contacted Kosharek last week in hopes of getting another angle on vernacular photography for our upcoming FAMILIAR STRANGERS show, which opens this Friday. The private collectors we had interviewed so far seemed delighted by the often unsolvable mysteries of found photographs. Did a professional archivist find an unknown image intriguing… or annoying?

A few days later, Daniel’s colleague Hannah Abeldeck ushered us onto an elevator and down to the basement of the Palace of the Governors. Abeldeck works as an image specialist for the archives, cataloguing, scanning and researching images in the collection of about 1,000,000 objects. The main room of the archives is packed with file cabinets and bookshelves. Sunlight streams down from a stairwell, making the subterranean space surprisingly bright.

“We weren’t a hundred percent sure what you were interested in, so I pulled some stuff to give you examples,” Abeldeck said, pointing to a teetering stack of files and a big green box.

To be honest, we weren’t sure either. We had no specific criteria when we were compiling photographs for FAMILIAR STRANGERS, which features compelling, mysterious images of diverse people and places. Unlike the scholars and history enthusiasts Abeldeck usually works with, we were more interested in questions than answers. In the following excerpts of our Q&A, Abeldeck provided us with a healthy helping of both as we explored a small corner of the “orphanage”.

You started at the archives last October. Was it intimidating to approach such a large collection?

I’ve worked in archives before, and for a rare book dealer. There are things about it that are not intimidating, but there are plenty of things that are. Partly, it’s the size of our collection. It’s huge. There’s stuff that’s really well processed, and then there’s stuff that’s hardly processed at all. There are so many different filing systems, so an original photograph can get put somewhere and be difficult to find again. There are systems by medium, by size, by when it arrived, by collection number.

Why were you interested in archival work?

I think that our ideas about the past are often very simple. They’re based on things like summaries that people wrote about what they think happened. Sometimes photographs are a way of going back and re-looking at the past that you can’t do with words. You can get some idea of the complexity of the past. There’s a book that I read called “The Past is a Foreign Country.” In some ways, this job is like being a tourist. It’s interesting to see what is the same and what is different, what has changed and what is new.

Orphan photos are catalogued in several ways: by location (left, New Mexico), collector (center, Forrest Fenn) or subject (right, portraits)

Where did the stack of orphan photos we’re looking at come from?

We have a set of collections that exist in this limbo land between the old cataloguing system and the new cataloguing system. We might know something about them, or they might just be a box of photographs sitting on a shelf. This box says “Forrest Fenn“, so he probably donated them. Some have a photographer’s name on the back and some don’t. The stack of files is catalogued by location or subject— “New Mexico Towns” or “Portraits”.

Is there a way to estimate how many of your photographs are “orphaned”?

No, there’s not. Most of the stuff that we have, we know at least one thing about, so they’re not completely orphaned. Usually we know the photographer. Their name will be on the back, or the collection will be from their studio. Sometimes we don’t know anything about the photographer, but we know the location. When we seek things out for our collection, we’re usually looking for things where we know the photographer or the subject matter. But people also donate stuff to us. Those items that come in bulk collections, we know less about. The date is usually the thing that is the least identified about a photo.

What is the attitude among archivists towards orphan photos?

Over the past 20 years, a lot of people who work in archives have adopted a philosophy called “MPLP.” That means “More Product, Less Processing.” It’s a way to deal with the huge volume of material that’s coming in. The volume of records that got created over the 20th century exponentially increased as the technology of production became cheaper. In the 1960s a photo archivist here might have spent four hours trying to identify a building in a photo. Now, we just don’t have time to do that. That’s one reason things get orphaned.

Mysterious beauty

The found photo collectors we interviewed find the element of mystery alluring. Do you get excited sometimes when you’re looking through orphan photographs, even though you don’t know their origins?

Yeah! I’ll be looking through 100 unremarkable photographs from the past, and there’s one that seems more interesting or outstanding than others. There might be something aesthetically different about that photograph, but we’re also looking for historically interesting things. It doesn’t have to be a historical event, it could be about social history: why are these people together in this scenario? There are all sorts of social or technological things that could be interesting, even with orphan photographs.

In a blog post for FAMILIAR STRANGERS, we wrote about different roles people take when they’re looking at vernacular photographs: voyeur, detective, surrealist, even humanist. What would you add to that list?

I’d add sociologist or social historian, particularly with the vernacular photography. We have a book called “Dressed for the Photographer” that’s a huge study of what people were wearing in daguerrotypes. You can date them based on their class and their region, so you can pin it a little more closely to the decade. It’s a way to find out what kinds of people passed through different places. We have portraits of Chinese men from Las Vegas, New Mexico that we don’t know much about, but their presence captures a bit of railroad history in the Southwest.

The photo collectors we interviewed also talked about the importance of bringing long-forgotten memories into the digital world. Do you feel similarly as an archivist?

One of my main job duties is digitization. If you wanted to see and study some of these things, you would have to come to Santa Fe, New Mexico on an afternoon between Tuesday and Friday. Through digital cataloguing, we can post that stuff online and people can search from their houses. However, we have over 1,000,000 images and we’ve digitized maybe 30,000 of them. There’s still a huge mismatch between what we have and what is searchable online.

Adelbeck flips through photographic glass plates in the archives. “As long as you don’t drop them, these will last forever.”

On the flip side, photo enthusiasts also stressed the importance of holding the physical object in their hands.

Having the original copy is very important for us in our ability to archive things. There’s something called digital obsolescence. For a physical photograph, if we put it in an archival mylar sleeve and keep them in a climate controlled environment, that is 95% of the preservation job. Digital objects are not that way, they need constant babysitting. Things periodically need to be switched over or upgraded. The CD is already an obsolete technology, so if you created a digital photograph in that format you have to migrate it to something else. With digital objects, there is a risk of the object disappearing within 15 years.

Do you have any stories of people identifying themselves or family members in an orphan photo?

I just posted a picture on Facebook last week of two kids playing baseball. We knew the photographer and the date, and we knew it was in New Mexico somewhere. Someone recognized his brother in the photo. It’s really cool when that happens, but it’s bound to happen sometimes. We have all of these photos of unidentified people, and someone out there must know who they are. Those people existed at some point.

Is it frustrating when you encounter photographs that have recently left the range of “living memory”?

It’s kind of interesting, because you start to understand the process by which photos get made, and how that affects what we can recover from the past. In the past, the occasions of photography were more constrained. You got a photo taken at an important event, like a wedding. As technology makes photography more accessible to the average person, you see a much larger growth of everyday captured moments that are not remarkable. At the same time, even within the proliferation of photography, there are things that happen that people don’t think to take pictures of. The process of painting a house might be interesting to future historians, but no one bothers to document that. There are a hundred billion photographs taken of the Santa Fe Plaza or the Palace of the Governors—and people are still taking them today—but there might be a storefront somewhere that no one has really photographed. It’s really interesting what people are choosing to document, and what they don’t document. We try to fill in those gaps by collecting photographers like Robert Christensen, a deliveryman who captured obscure stretches of road in rural New Mexico.

So this is just the tip of the iceberg?

Oh, yes. We have many, many, many more unidentified photos. If you needed pictures of ancestors and didn’t have any of your own, you could just come pick some. (laughs) “This is my great grandmother.”

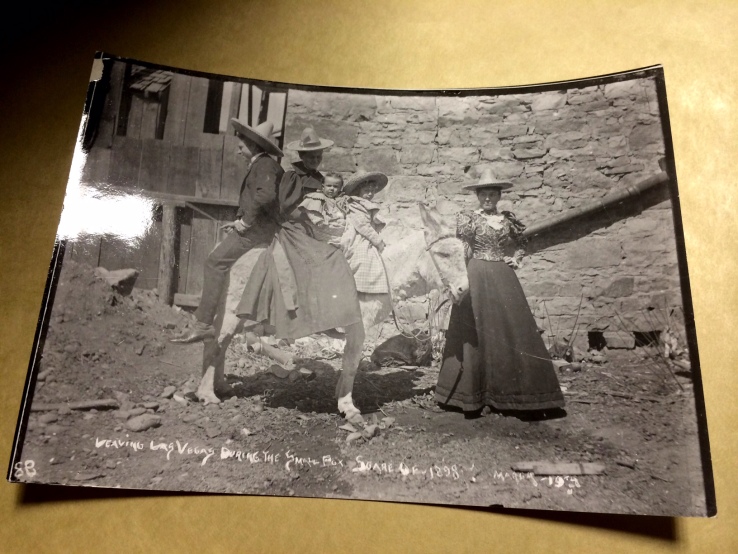

Caption: Leaving Las Vegas During the Small Pox Scare, 1898; filed under Transportation, Land, Burros

You can follow Abeldeck and Kosharek’s exploits on the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives Facebook and Tumblr pages. Also, make sure to come to the opening of FAMILIAR STRANGERS: Vernacular Photography this Friday from 5-7 pm. Read more about the show in this week’s Santa Fe Reporter.

[…] There’s more; it’s a great interview. Give it a read here. […]