It was 1901 in New York City, and photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was busy preparing an exhibition that would shake the foundations of the art world. He had worked for years—often to the point of physical exhaustion—to elevate photography to the stature of fine art. A series of juried photography shows, judged mostly by painters, had popularized the aesthetic of pictorialism. Pictorialist photographers approached their art like a painter or illustrator, playing with focus and exposure in innovative ways and even marking the surfaces of their images. The idea was to “make” an image rather than “take” it, projecting emotions into the scene and onto the viewer.

Stieglitz and his friends saw the need for yet another leap forward in this new era of photography. They would mount a show composed entirely of photographs, and judged only by photographers. Or rather, it would be judged by one photographer: Stieglitz himself. He put together the show in two months and dubbed it the Photo-Secession, intending to secede from old conceptions of both photography and fine art. The exhibition was an enormous success, and gave Stieglitz the momentum to launch a photography journal and gallery to promote his ideas.

From left: View of Stieglitz’s Little Galleries of the Photo Secession, which opened in 1905;

Edward S. Curtis in his adventure clothes.

Thousands of miles away in Seattle, Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) was just beginning his photography career. Curtis grew up in Wisconsin and built his first camera when he was a teenager. At 17 he apprenticed in a photography studio in St. Paul, Minnesota, and when his family moved to Seattle in 1887, he bought a partnership in a portrait studio. Over the next few years, he began photographing Native American people of the Washington territory, some of them relatives of Chief Sealth and other important leaders. These early portraits and genre scenes inspired a 30-year adventure through the American West, during which Curtis and his team recorded the lives of over 80 tribes in photographs, writings, recordings and sketches.

Curtis’ expeditions, which he recorded in a series of volumes called The North American Indian, kept him far away from the epicenter of the American avant-garde where Stieglitz resided. “He was an outsider, too far removed from the photographic salons to court or count on ready shows and reviews that had instituted pictorialist photography,” writes Gerald Vizenor in an essay on Curtis. However, it’s this aesthetic that ties Stieglitz and Curtis together in art history.

“Curtis kept abreast of national, even international, trends in photography—and in the visual arts more generally,” writes Mick Gidley. “His early writings for Seattle magazines reveal that he absorbed much from Pictorialism in photography, including the example of Alfred Stieglitz, the founder of the Photo-Secession.” Curtis’ earliest photographs of Native peoples feature the soft focus and sepia tone of some classic pictorialist images, and present his subjects as stoic archetypes of a vanishing culture. In his many adventures, Curtis often posed his subjects and manipulated images to fit his vision of the tribes he was portraying. These techniques have earned Curtis praise as a pictorialist, but have also stirred up controversy. Curtis called himself an ethnologist, but the aesthetically powerful images he created didn’t always aim for scientific accuracy.

In the collection of photographs below, we’ve reunited Curtis with his pictorialist roots, placing some of his most iconic images among significant works by Stieglitz and his contemporaries. As you view the images, ponder Curtis’ position as an outsider during his lifetime, and his new place as a pictorialist in the art history books…

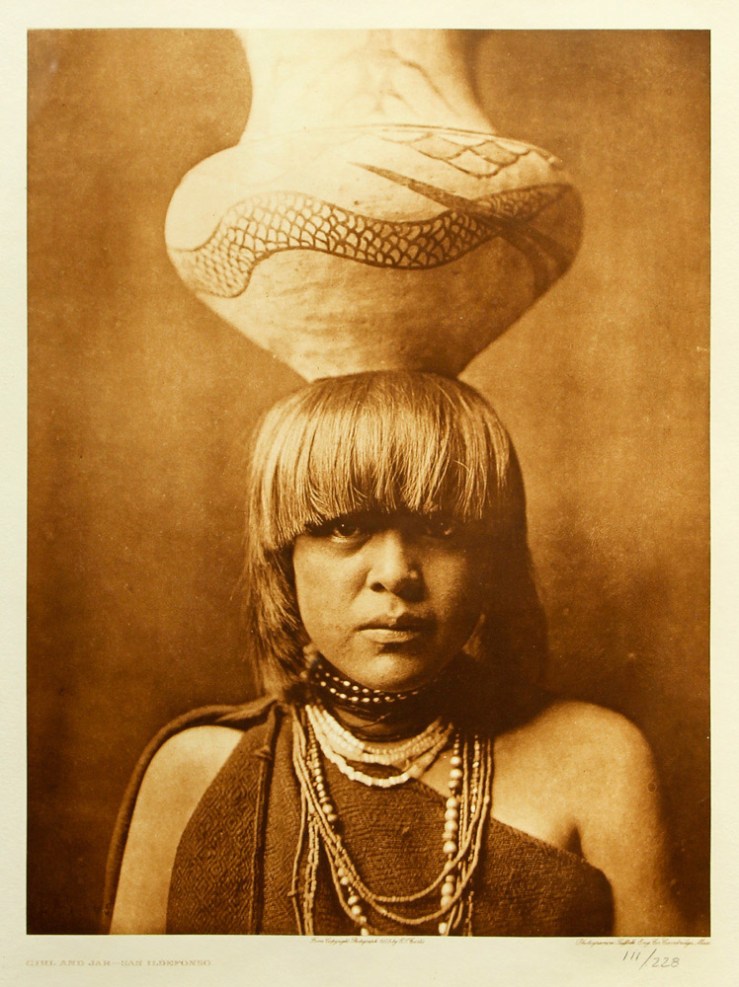

Edward S. Curtis, Girl and Jar, Photogravure

Adolph de Meyer, Marchesa Casati, 1912

Edward S. Curtis, Apache Medicine-Man, Photogravure

Henry Peach Robinson, Fading Away, 1858

Edward S. Curtis, The Rush Gatherer, Photogravure

Alvin Langdon Coburn, Spiderwebs, 1908

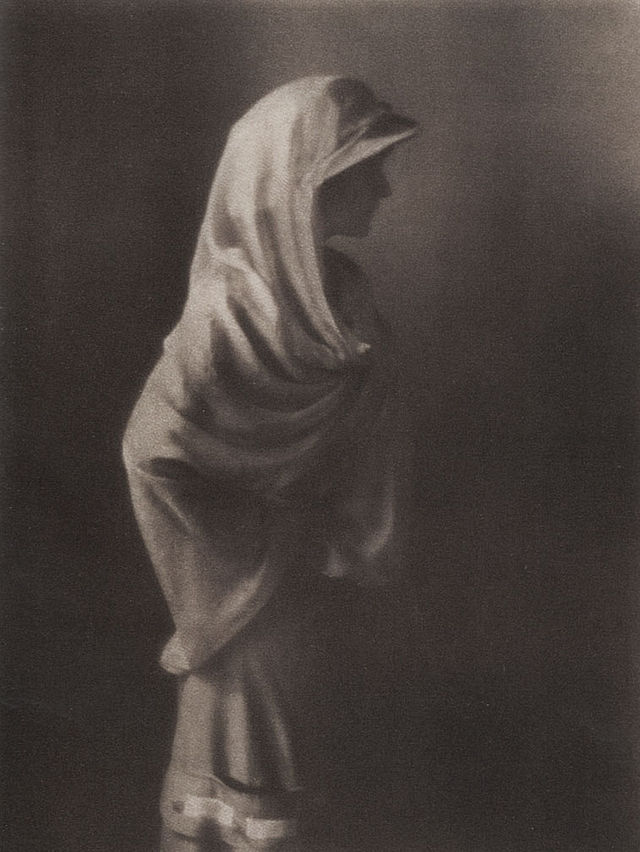

Edward S. Curtis, Waiting in the Forest— Cheyenne, Photogravure

Paul Haviland, Doris Keane, 1912

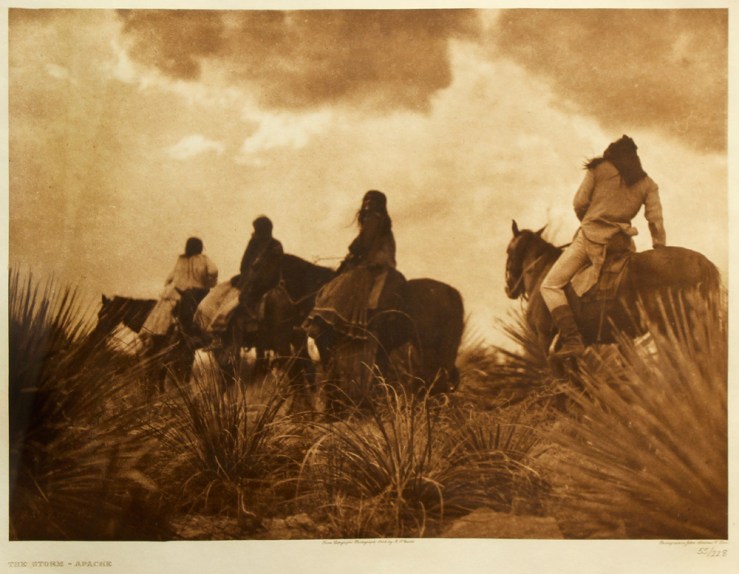

Edward S. Curtis, The Storm-Apache, Photogravure

Alfred Stieglitz, The Terminal, 1893

Click here to learn more about Edward S. Curtis, his adventures and the rediscovery of his work in the 1970’s, and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for daily gallery news.