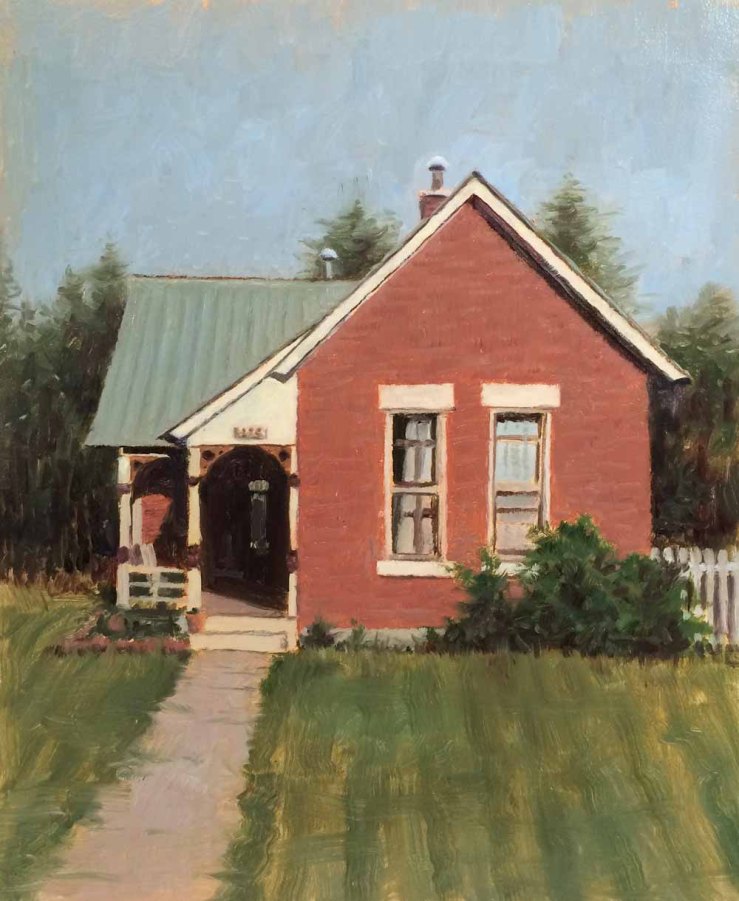

Untitled, Unknown

“A photograph is usually looked at—seldom looked into,” said Ansel Adams. When it comes to the pictures in our upcoming show, there’s no other option but to dig a little deeper.

FAMILIAR STRANGERS: Vernacular Photography, opening Friday, May 16, is not your typical Matthews Gallery show. The artists who created our collection of found photographs never got the recognition that Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec or Renoir did, but there’s no denying their aesthetic sensibilities.

That’s what has kept us digging through estate sales, thrift shops, antique stores and attics for years. We’ve amassed quite the collection of vernacular photographs, also known as “found” or “orphan” photos, and we’re not alone in our scavenging habits. Our friends on social media understand the great allure of the hunt.

“Looking at so many old and found photographs I often think that, ‘I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,'” writes Paul Jackson, who maintains the Flickr group Found Photographs. “The person behind the camera has seen these things, lived that life..you know, we can sometimes almost taste it.” We asked several other photo finders what they love about the pursuit, and they all had equally passionate answers.

Vernacular photography presents unique challenges to the viewer, asking us to shift between different roles to grasp what we’re seeing. Our first impulse is often voyeuristic. We can’t resist a peek at someone’s intimate moment, and we swiftly draw conclusions about what’s going on. In the image above a baton girl gawks open-mouthed at a band boy, but he looks resolutely away. Is this a tale of unrequited love?

Society often slaps us on the wrist for our voyeuristic tendencies. In his brilliant essay on found photography Dr. Barry Mauer of the University of Central Florida says this instinct is something we should indulge.

“At first sight, most of these pictures are hilarious or tragic or both,” writes Mauer. “Voyeurism allows me to experience these reactions from a comfortable distance.” However, Mauer cautions against stopping there. Voyeurism often comes hand-in-hand with judgment and categorization. Stereotyping these mysterious individuals cuts us off from a rich world of visual mysteries. Time to pull out the magnifying glass.

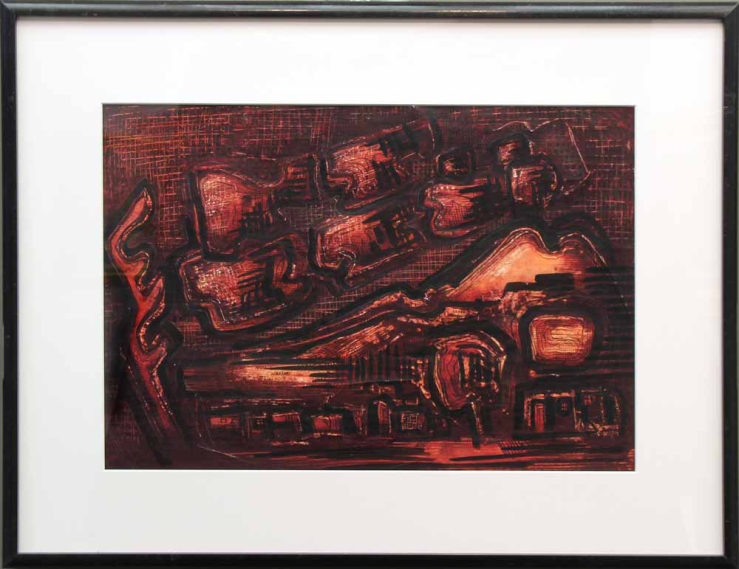

Untitled, Unknown

If we act as detectives, this simple portrait holds a lot of hints about the bicyclist and her photographer. Did you notice the bandages on her knee and arm? If those are recent wounds, perhaps she’s just learning how to ride. It’s difficult to tie a forearm bandage on your own. Maybe the person behind the camera is her teacher and medic? On the other hand, the bags on the handlebars hint at a different adventure. One of them looks like a canteen. Could the other hold snacks for a picnic?

Teasing out these details is invigorating. To take it one step further, note the composition of the photograph. The front wheel is cut off and part of the path is visible behind the girl. This perspective, when combined with the subject’s bent posture and excited face, lends the photo a sense of forward movement. Our mysterious photographer has imbued a picture of a static bike with surprising dynamism. Was that his or her intention?

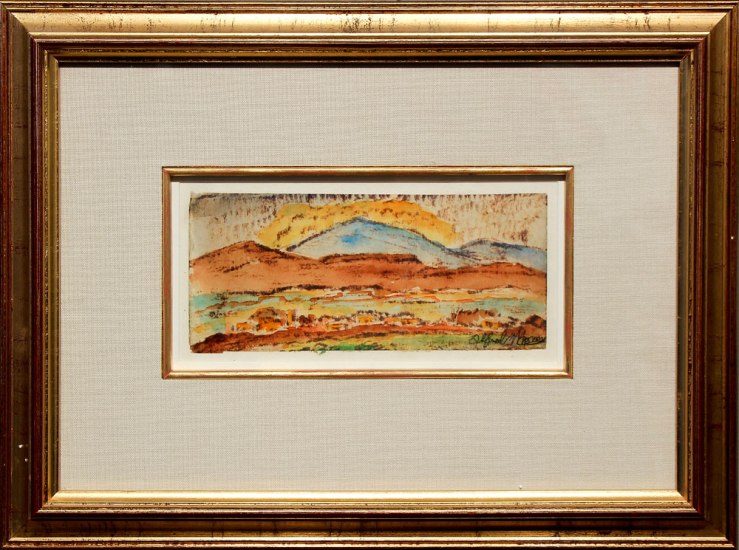

Untitled, Unknown

Of course, in the end we’ll probably never know if our inferences are correct. Who better to help us surmount our fear of the unknown than the surrealists? André Breton and his friends were inspired rather than daunted by impenetrable mysteries. They sought out fragments of culture, watching films from between their fingers to try to catch discreet details and writing stories based on dreams they had about real experiences.

Both techniques allowed them to focus on details they otherwise would’ve ignored. In the photo above, our interest in the group in the foreground distracts from the odd figure standing in the far background. Cropping the photo brings up a whole array of new questions.

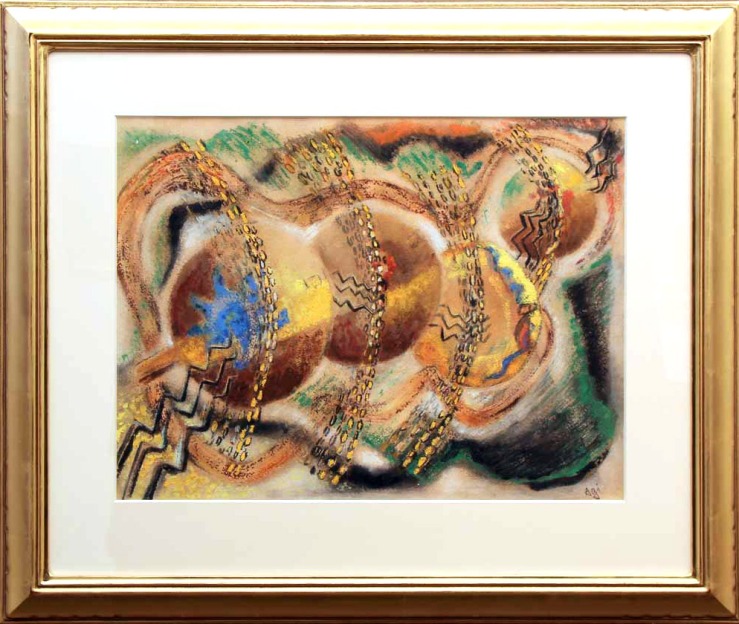

Detail of previous photo

In a broader context the entire photo is a fragment. The man in the foreground’s stern expression stands alone, isolated from what happened before or after. Perhaps he cracked a smile a moment later, but this short glimpse of his day at the pool has a foreboding air to it.

“The surrealists used fragmentation as a means to knowledge, discovering significance in the fragment that had been concealed in the contextualized whole,” Mauer writes. It’s not hard to trace the progression of this thinking to Marcel Duchamp’s use of found objects, or to the Dada artists’ repurposing of vernacular photos in collages (more on all of that in an upcoming blog post).

In the end analyzing and relating to the “characters” in these photographs helps develop our skills in another field: humanism. It’s amazing how connected we can feel to a person we’ll never meet, and how powerful our feelings of empathy and sympathy can be when we exercise them. Look long enough, and you’ll start to imagine that these familiar strangers are looking right back.

Step into the shoes of a voyeur, detective, surrealist and humanist at FAMILIAR STRANGERS: Vernacular Photography, opening Friday, May 16. Also, make sure to check out our fascinating interview with four found photography collectors and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr for more gallery news!