NEW LANDSCAPES, NEW VISTAS: Women Artists of New Mexico ends on May 31st. Over the course of the exhibition, we’ve blogged about early women potters of New Mexico and their influence on women artists who migrated here. Here are the tales of four 20th century women who came from near and far to turn over a new leaf—or a new canvas—in the Land of Enchantment. Through their efforts, the Santa Fe and Taos art colonies were forever changed.

Beulah Stevenson (1891-1965) grew up in Brooklyn Heights, New York. After studying at the Pratt Institute, she enrolled at the Art Students League where John Sloan became her mentor. Sloan invited Stevenson to summer in New Mexico, where she was inspired to create modernist landscapes and wild abstract works in the vibrant palette of the Desert Southwest. She returned to New Mexico many times throughout her life.

Stevenson worked as a printmaker, painter, illustrator, art teacher and Brooklyn Museum curator. She was a staunch advocate of modernism and the avant-garde, working with the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors and numerous other artist organizations.

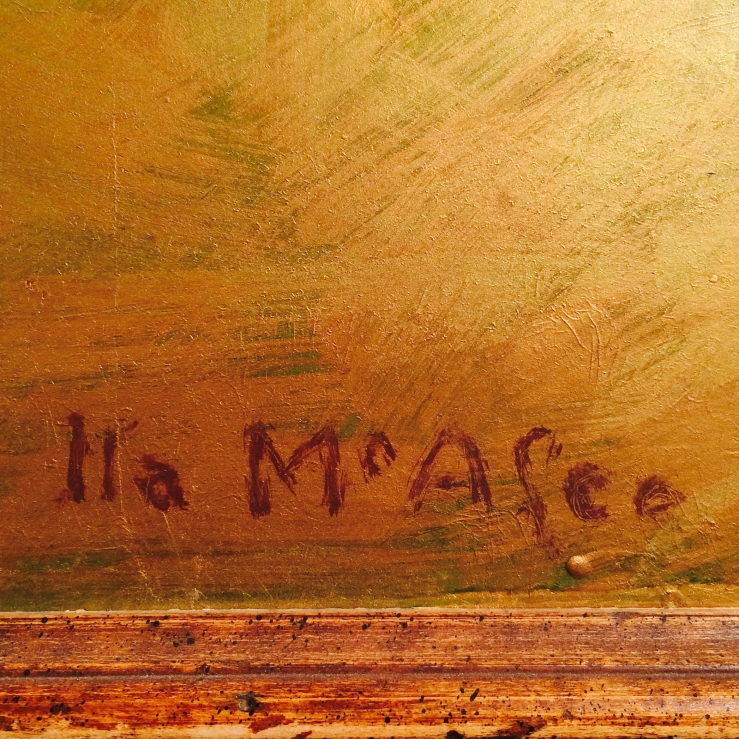

Ila McAfee (1897-1995) was born in Colorado, and first visited Taos on a road trip to California in 1926. She fell in love with the mountain village and its thriving art scene, and settled there with her husband Elmer Turner. They quickly befriended influential members of the Taos Society of Artists such as Blumenschein, Berninghaus, Hennings and Higgins. McAfee was a rare Western-born artist in Taos, where many artists were transplants from the East Coast. She captured the spirit of the West through her paintings of sweeping landscapes and the wild horses that roamed them.

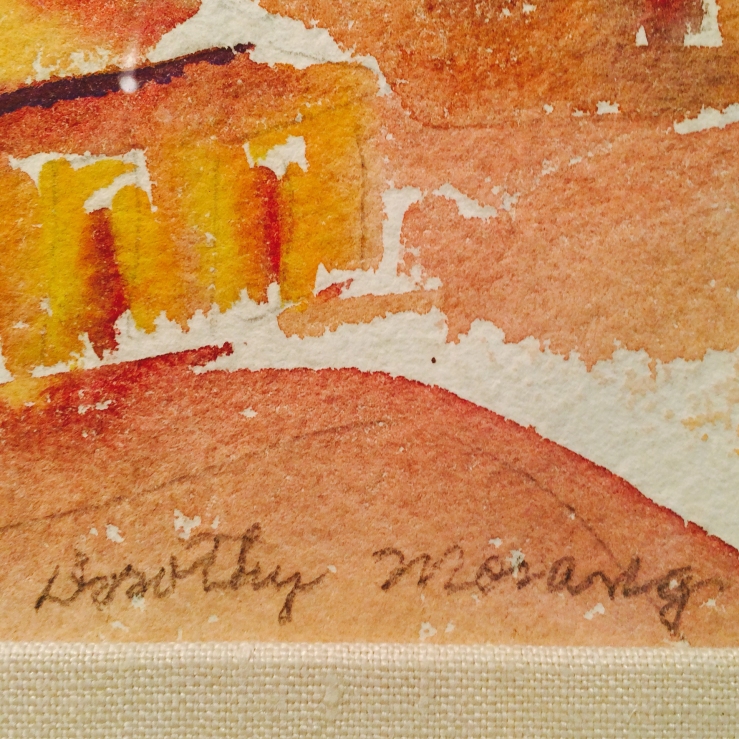

Dorothy Morang (1906-1994) was born in Richmond, Maine. She met Alfred Morang in 1925, while studying at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. Alfred was a violinist and Dorothy a pianist. They married on June 13, 1930 and moved to Portland, Maine soon after.

The couple moved to Santa Fe in 1937 in an effort to alleviate Alfred’s tuberculosis. In the City Different, they landed in the center of a colorful circle of artists. They threw Saturday night salons at their home not far from Canyon Road and taught music and painting to make ends meet.

In addition to painting, Dorothy Morang worked for many years at the New Mexico Museum of Fine Arts, primarily as a curator.

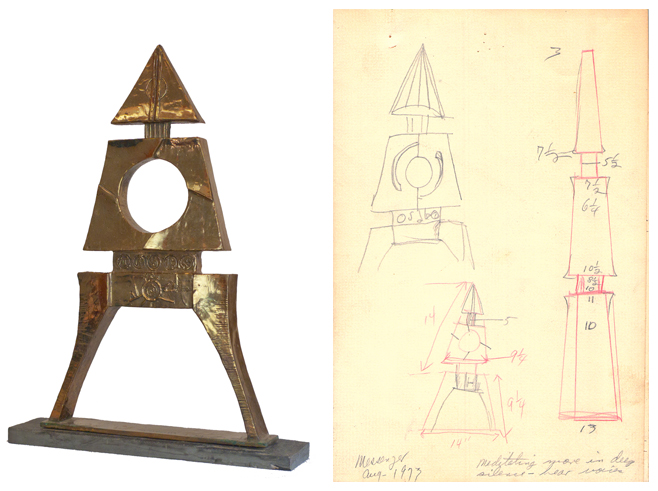

In her three decades in Santa Fe, beginning in 1972, Doris Cross (1907-1994) was known as the City Different’s “most avant-garde artist.” An excerpt from a 1990 biography by Anna Christine Hansen traces the artist’s New York roots and her early days in New Mexico:

Doris Cross began her career in New York City with the Art Students League. After meeting Hans Hoffman, who was known for encouraging artists to investigate their own ideas and unique styles, she went to the Hans Hoffman School of Art. “Hans Hoffman was it,” Doris said of him as a teacher. “…The possibility of discovery! That was the important thing, discovery.” […]

In the mid-1940’s, Doris received the Turner Award from the National Association of Women Artists for a painting which made the leap to large-scale. […] Like many women, she was married and raising a family in the 1940’s—a son and a daughter. In the early years of her development, while living in Woodstock, she painted a series of Madonnas. Later, she taught painting in a basement in Brooklyn in order to afford supplies to paint.

Click here to view all of the artwork in NEW LANDSCAPES, NEW VISTAS, and make sure to stop by tomorrow if you haven’t seen it. You can connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for daily gallery news.