Candid shots of the secretive artist with her sculpture “Survivor“, Hannah Holliday Stewart archives

At last Friday’s opening for Hannah Holliday Stewart: An Artistic Legacy Rediscovered, art enthusiasts who saw the press coverage for the show came armed with a diverse array of questions.

“What was her family like?”

“Where did the full-scale models in those photos end up?”

“What’s ‘Ockum’s Razor‘ ?”

“Who’s Brad?”

Of course, the most frequent question was also Stewart’s most impenetrable mystery: why did the sculptor abruptly leave Houston, the launching point and epicenter of her nationally renowned artistic career? In our explorations of Stewart’s archives over the past few weeks, we’ve stirred up as many questions as answers.

Stewart was resolutely private, preferring to tightly focus on her artwork in interviews, exhibition materials and even her diaries. A catalog for her 1975-6 solo exhibition at the Houston Contemporary Arts Museum provides little more information on Stewart’s personal life than a birth year and a brief sketch of her educational history.

“Hannah was a very private person with a lot going on in her head,” close friend Dayton Smith told us. “I learned when to be around her and when not.”

Many of Stewart’s works, on the other hand, were always in the public eye. Kids lounged in the crook of her 11-foot sculpture in Hermann Park, students at St. Thomas University studied under her concrete-and-steel work on campus, and politicians were often photographed beside her “Libertad” fountain as they passed through the courtyard of Houston’s World Trade Center building.

For this week’s blog, we’re taking cues from Stewart’s ghost and focusing on the rich universe of her sculptures. Look below for new insight on five artworks, with behind-the-scenes materials from the artist’s files.

Preparatory sketch for ‘Atropos Key’ and full-scale plaster model in Stewart’s studio

‘Atropos Key’ remains Hannah Holliday Stewart’s most well-known sculpture in Houston. Our maquette’s monumental counterpart stands on a hill in Hermann Park, measuring at 11 feet tall and 1,200 pounds. It debuted to much fanfare in 1972. From the Houston Chronicle’s August 11, 1972 edition:

“Out on the hill beyond Miller Theatre the blanket lollers who tune in to night concerts and shows from a horizontal position will have fresh ‘company.’ Overlooking the stage, now, is a bronze vertical figure.

‘Atropos Key,’ the title of which derived from one of the three fates in Greek mythology, was given to the city by Mrs. Patricia S. Woodward of Houston.

Strollers in the park may well stare at it and wonder what it all means…. Miss Stewart’s piece, in its new location, deserves the looking at, the ‘experiencing’ and the consideration of its meaning for you. Is it birth and, more encompassing than that, renewal?”

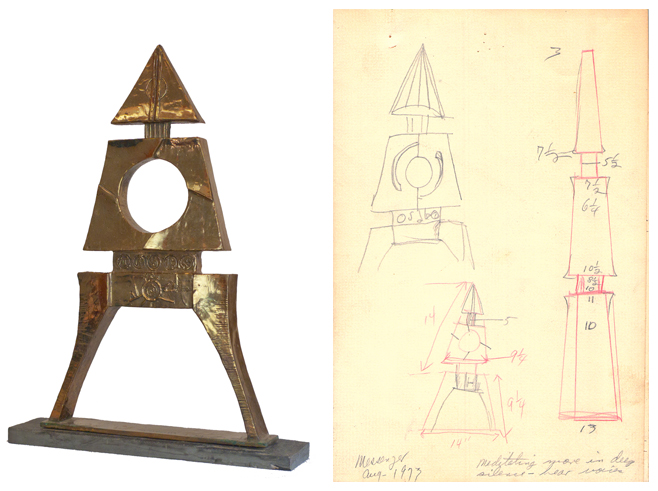

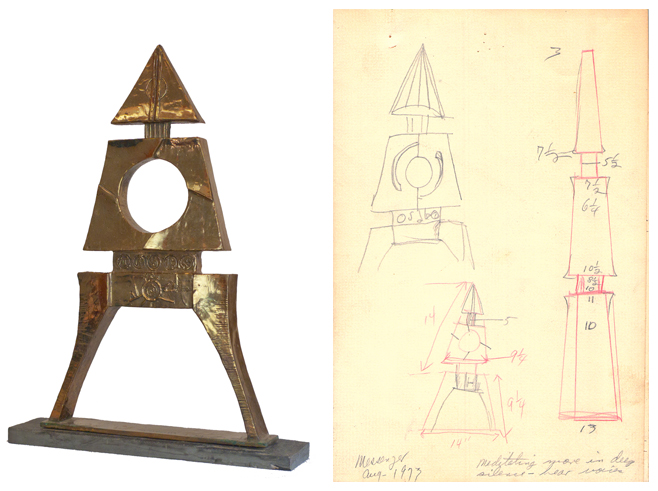

Preparatory sketch for ‘Messenger’ dated August 1973

Preparatory sketch for ‘Messenger’ dated August 1973

Stewart’s ‘Messenger’ appeared on the cover of Houston Arts Magazine’s performing arts edition in October, 1982. Stewart was a fan of Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, and often listened to classical music in her studio.

A blurb inside the magazine traces the musical roots of ‘Messenger’:

“Sculptor Hannah Stewart… sees her work as an artist’s shorthand using symbols to communicate complex and abstract ideas— like a composer uses the symbols of musical notes to convey a spiritual idea in a sensuous form.

In Messenger… Stewart sees a parallel between the structure-strength-shapes interplay of her work and compositions played by Nathan Milstein and Bella Davidovich.”

Original typewritten label for ‘Ockum’s Razor’

Original typewritten label for ‘Ockum’s Razor’

Stewart was known for her mythology-inspired artwork, but that was far from the only subject she explored.

“Her studies in literature, mythology, metaphysics, esoteric philosophy, religion, science, astrology, dance and yoga suffuse her output, revealing in form and textures,” wrote Stewart’s friend Dayton Smith in a letter to the gallery.

In ‘Ockum’s Razor’, Stewart turned to science for inspiration. The title refers to a problem-solving principle devised by 14th century logician and Franciscan friar William of Ockham (c. 1287-1347). The principle states that “Entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily.” In other words, the simplest path to an answer is the best one.

Maquette and full-scale versions of ‘Survivor’

An article about Stewart’s work appeared in the local paper of her childhood home of Birmingham in 1994. In the story, Stewart explains the inspiration for ‘Survivor‘. From the August 1, 1994 edition of the Birmingham Post-Herald:

“I was teaching welding at the university, and I’d go to the welding studio and talk to friends of mine, and there were a lot of men coming down from Detroit who’d lost their jobs, and they were so tense and angry about having to reform themselves, to learn to do welding or something else at the age of 55, after having been an auto worker. I reacted to that force within them, and the drastic changes people have to make to survive.”

Polaroid of Hannah Holliday Stewart in her Albuquerque studio working on ‘Einstein’s Song’

Stewart was 80 years old in the Polaroid above and still hard at work on her bronze forms, though she never exhibited again in her lifetime.

Here’s an excerpt from a typewritten artist statement Stewart wrote a year later:

“For me, the image should be an intellectual and emotional symbol plucked from the fringe of the imagination, it should suggest a classic truth and not be confused with social comment. The image at its most successful strikes a common chord of sensations in every viewer, and yet leaves each viewer with his/her own particular interpretation.”

See Hannah Holliday Stewart: An Artistic Legacy Rediscovered through July 18, and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for more information on the artist.

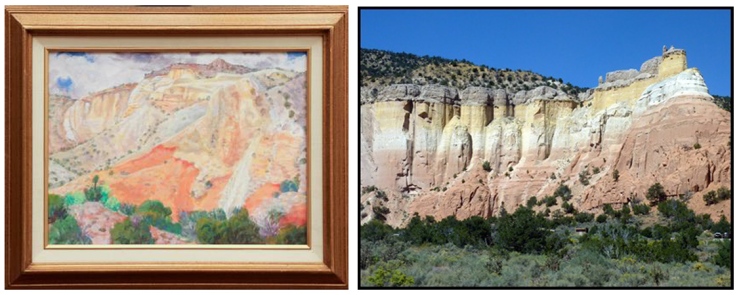

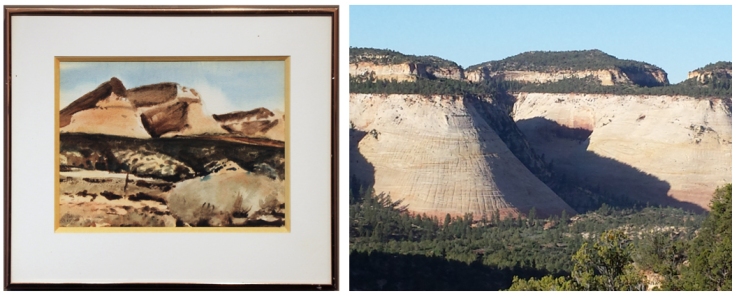

This Alfred Morang painting may show artist Olive Rush’s garden on Canyon Road. Rush and Morang were close friends. Compare to the photograph at right.

This Alfred Morang painting may show artist Olive Rush’s garden on Canyon Road. Rush and Morang were close friends. Compare to the photograph at right.