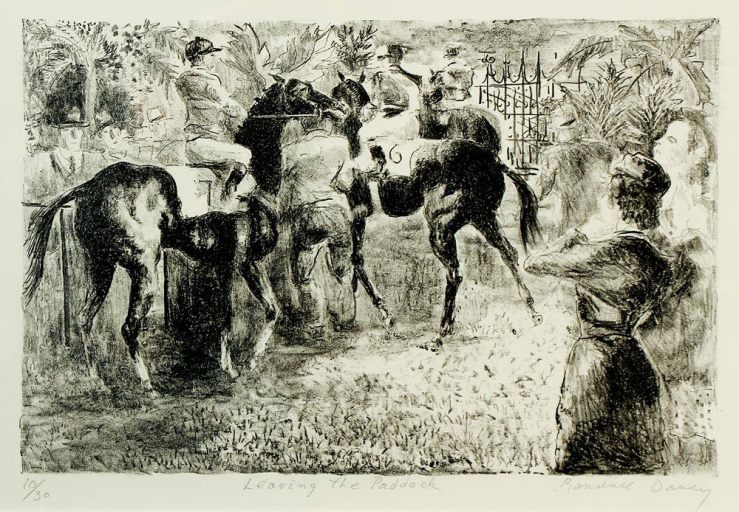

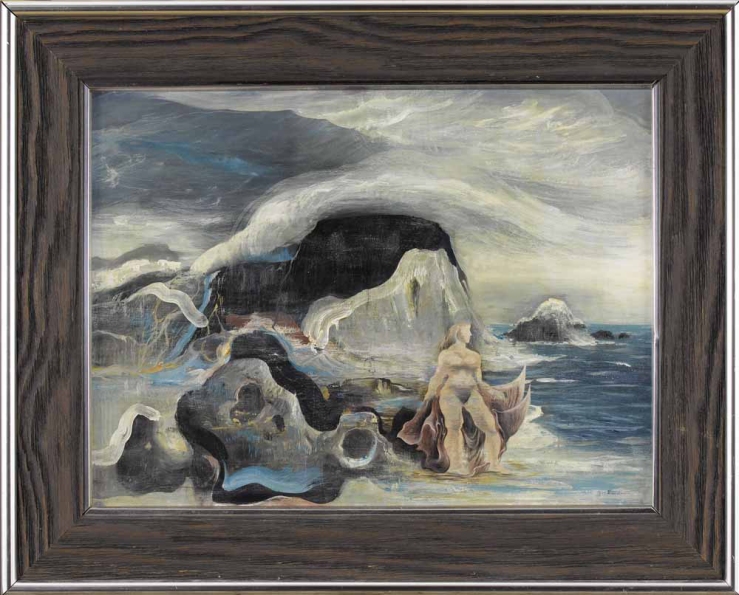

Alfred Morang, 1952

Alfred Morang, 1952

“After Morang’s death, all of a sudden people started to realize that he was a great artist. People regretted that they didn’t pay enough attention to him,” Santa Fe art collector Paul Parker said at the end of our interview last week.

As Parker will tell you, Alfred Morang’s death in a Canyon Road fire in 1958 was the end of an era in Santa Fe. From his arrival in 1937, Morang had helped cultivate a vibrant art scene in the City Different. His house parties of the 1930’s and 40’s earned him a reputation as “one of Santa Fe’s… most colorful Bohemians,” as the Santa Fe New Mexican dubbed him in his obituary. Morang was a masterful painter who drew inspiration from the French Impressionists, and a talented teacher who passed his knowledge to the next generation of Santa Fe artists. He was a great writer, musician and radio broadcaster.

However, towards the end of Morang’s life, he and his wife Dorothy divorced and he became increasingly isolated. He spent most of his time fervently painting in his Canyon Road studio. Santa Fe artist Bill Tate had this recollection of a frigid winter in the 1950’s:

Oh my, it was cold! The snow was pouring down unmercifully and as I walked into Alfred’s tiny studio, I pushed paintings aside to make a path, then found them sliding in behind me as I penetrated the cache of completed canvases. It appeared that paintings were everywhere. There in the middle was Alfred, happily painting away, bundled up like a Siberian monk—galoshes, muffler, sweater, heavy top coat which came to his ankles, and a woman’s hat pulled snuggly down over his ears and neck.

The studio had a sky light, but where the glass was supposed to be, there was none. Alfred had hung an old muslin sheet over the opening to shut out the falling snow. Evidently Alfred had let the fire go out in the small space heater. Or maybe had forgotten to pay his gas bill. I don’t know. But it was awful. I had been there just a few minutes when the muslin partially ripped loose from the ceiling and began flopping in the wind. Snow dumped all over Alfred as well as the canvas.

Alfred never looked up, never stopped painting. His blue-cold hands kept mixing painting and dabbing it on the canvas. Occasionally, he would lean back to assess the effect, but throughout, he was totally oblivious to my presence… or the muslin that danced in the bitter breeze.

I attempted to speak, but only a chatter came out. I retreated to the warmth of my own studio. To the day he died, Alfred never knew I was there.

This somber image of an artist in the winter of his life is not how Parker likes to think of Morang. Soon after he first visited Santa Fe in the 1990’s Parker developed a fascination for the Santa Fe icon that has taken him on many adventures, including a national treasure hunt that inspired our latest exhibition. The artifacts Parker discovered will appear alongside artwork by Morang and his contemporaries in our December 12-26 exhibition MORANG AND FRIENDS, evoking an era full of crackling creativity. Morang stood at its warm heart.

In the story below, Parker captures the Santa Fe zeitgeist before and after Morang’s death, and travels to Paris to complete a mission in Morang’s memory:

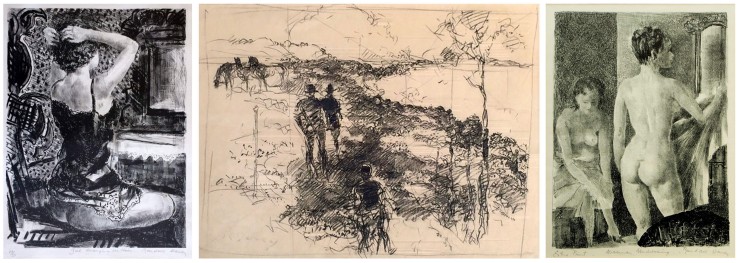

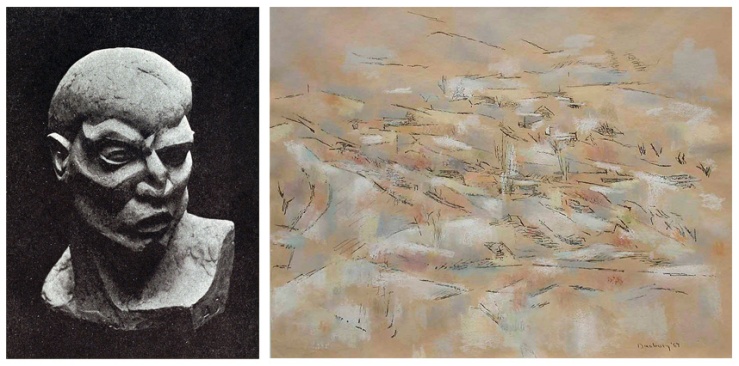

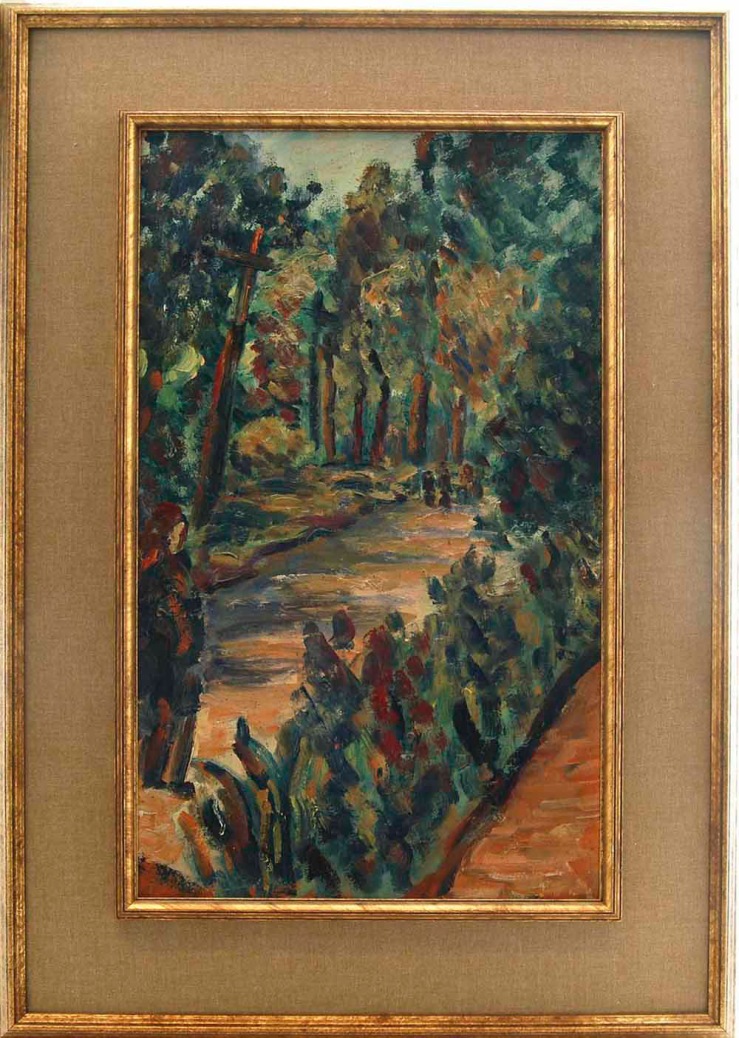

Alfred Morang, Untitled (Santa Fe Hillside) 1949, Oil on Canvas

Alfred Morang, Untitled (Santa Fe Hillside) 1949, Oil on Canvas

HUNTING FOR ALFRED MORANG

by Paul Parker

I had been thinking about this mission for a long time and I finally find myself in the library seated in front of this antique microfilm viewer the size of a small refrigerator and I have loaded the reel containing the early 1958 issues of the Santa Fe New Mexican.

I was not sure why I had this unremitting need to know more about Alfred Morang. I had first seen his work painted on the adobe walls across from the bar in El Farol on Canyon Road and in Maria’s on Cordova, but I know the real inspiration came from my good friend Jim Parsons in Taos. Jim was an art dealer and appraiser forever and a friend and mentor for 20 years. When he mentioned that Alfred Morang was one of his favorites I knew I needed to pay attention. It was like Willy Wonka telling me about one of his favorite chocolate bars.

It helps that Alfred was such a compelling man, so well versed in music and literature as well as painting. He was the youngest person ever to perform a solo violin concert in the prestigious Jordan Hall in Boston. He was also an accomplished writer. The London Times once called him one of America’s leading non-political short story writers. Erskine Caldwell was a friend of his and he often visited Alfred and his wife Dorothy in Santa Fe. Alfred’s short stories and poems were published alongside Frost, Poe and Mark Twain. I do know the main reason I am so drawn to him is that his art touches me. Behind that art is Alfred’s story, his life experience and that is what drove him to create the art that Jim and I and many others enjoy so much.

Alfred Morang, Untitled (Portrait of a Woman) 1950, Oil on Board

Alfred Morang, Untitled (Portrait of a Woman) 1950, Oil on Board

There is a very sad part to his story and it is that part that drew me to the library. Alfred Morang died in a fire in his Canyon Road apartment studio on a cold January night at the age of 56. I had wanted to come here to the library and read the January 29, 1958 issue of the Santa Fe New Mexican for some time. I wanted to know the details, I wanted to read what people said, I wanted to know what page it was on and how big the article was. I was scrolling through the microfilm and as I started approaching the day he died I realized I was reading the papers that he probably read unaware he only had days to live.

The closer I got to the issue of the paper I had come to see the more time I took reading the articles and I even started reading the ads. I lingered the longest on Tuesday’s edition dated January 28, 1958. That was the last paper Alfred could have read.

There was an article on that day that I am sure must have caught Alfred’s eye and the headline read, “French Ballet loses Backing”. Alfred never made it to Paris, but his heart was there. His heroes were the French Impressionists and he considered himself to be one of them. Monet and Bonnard were his favorites. The article explained that the French Education Ministry had withdrawn the government subsidy for the production of Francoise Sagan’s ballet “The Broken Date”. The ministry’s action followed a storm of protest. Apparently one dance was performed in a bathroom setting designed by painter Bernard Buffet and was described by some critics as scandalously erotic. I would like to have gone to Paris with Alfred and attended that performance. A French ballet with a bathroom setting designed by Bernard Buffet coupled with scandalously erotic, I am sure we both would have enjoyed that.

That Tuesday the Lensic was showing “Pal Joey” starring Rita Hayworth, Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak. Kaune’s was having a sale featuring Pork Chops at 59 cents a pound and Swanson’s Pot Pies at four for a dollar with your choice of chicken, turkey or beef. Cherry Motor’s at 607 Cerrillos Road had an ad for the new Rambler American for $1789. The ad proclaimed that one had been driven from New York to Los Angeles using only 80 gallons of gas averaging over 30 mpg. I remembered that time. One week before this ad ran I had celebrated my 12th birthday and becoming a teenager was in sight. Unlike today I was looking forward to getting older and that was the time I began thinking about cars. Chevrolet had just introduced the 283 V-8 a year earlier in the now iconic 1957 Chevy. The fuel economy push left over from the war was fading fast and the Plymouth Hemi and the “Little GTO” were on the horizon. The economical 6 cylinder Rambler American never had a chance.

Alfred Morang, Pecan Grove, Oil on Panel

Alfred Morang, Pecan Grove, Oil on Panel

I read every bit of that Tuesday’s paper. It was as if I felt that Alfred would be okay as long as I did not turn the page, but I knew it was time to see what I had come to see. I took a last look at the classifieds and marveled at an ad for a 2-bedroom adobe with wall-to-wall carpet “close in” for $16,500 and then I hit the button and watched the microfilm reel turn slowly.

The first thing I saw positioned on the top left side of the front page of that Wednesday edition of the Santa Fe New Mexican was a large photograph of a cat crouching on the corner of a charred mattress. The rest of the bed was strewn with papers and tubes of paint. Underneath the right half of the photo was a caption “Mourning for Her Master…This lonely cat was found wandering through the charred ruins of the home of her master Alfred Morang who died in the fire early this morning. The cat is on the bed where he died.” Morang’s friends had commented on his love of cats and noted that he often went hungry himself so he could afford to feed them. Two other cats perished in the fire with him. Unfortunately I discovered that the cat on the mattress in the picture had to be put down because it had extensive lung damage. There was also a picture of Alfred. A cigarette in a holder was hanging from the corner of his mouth dangling over his scraggly beard and he was wearing a black hat with a brim that was tilted slightly to the left making him look decidedly like an artist and decidedly French. The story next to the photo read “Well Known Artist Dies In Home Fire… Alfred Morang, 56, one of Santa Fe’s best known and most colorful Bohemians died at about 1:30 am last night in a tragic fire at his home in the 600 block of Canyon Road.” Friends reported they had last seen Alfred in Claude’s bar around midnight. His apartment was just up the alley out back.

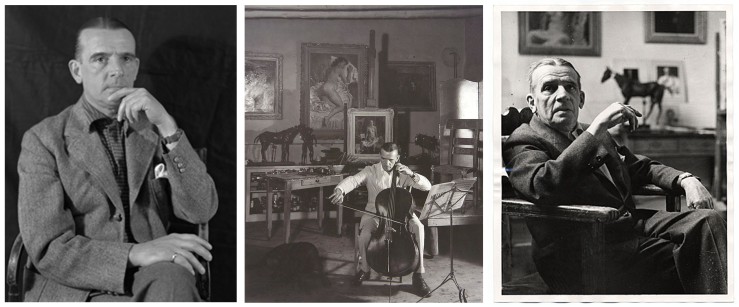

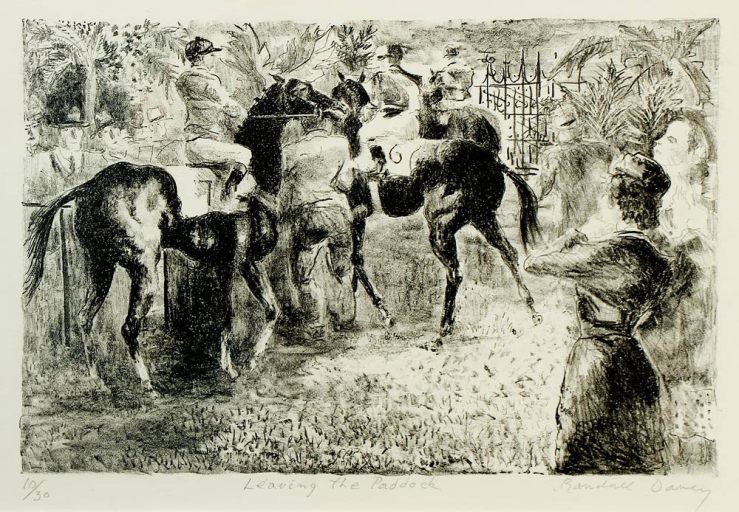

Five days after the fire the New Mexican noted…“Funeral services were held Saturday at the Fairview Memorial Park Crematorium in Albuquerque for Alfred Morang, widely known Santa Fe artist, writer and critic who was burned to death early Wednesday morning in a fire at his home here. The body was escorted to Albuquerque by a group of close friends, including Randall Davey, Will Shuster, Harlan Lizer, Walter Dawley and William Currie. Alfred was transported in a Spanish Colonial coffin made by Abolonio Rodriguez, custodian of the art museum.”

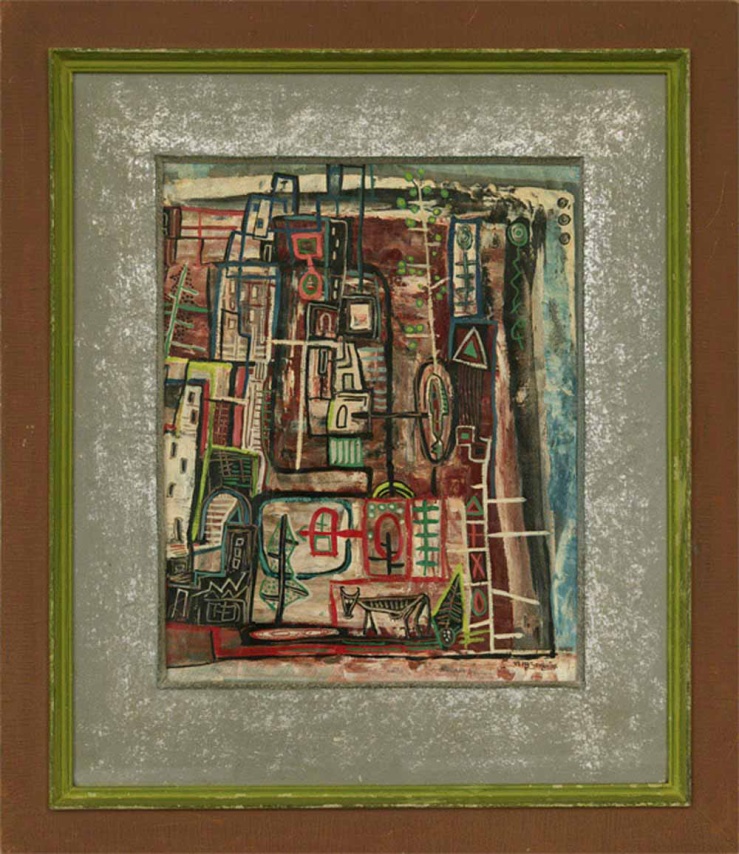

Alfred Morang, Guadalupe Plaza 1947, Oil on Board

Alfred Morang, Guadalupe Plaza 1947, Oil on Board

Alfred was born in Ellsworth, Maine in 1901 and came to Santa Fe in 1937. Like many who came here he suffered from TB. He immediately became a fixture in the Santa Fe art scene. He wrote a weekly column for the newspaper and he produced a weekly radio program for 17 years on KVSF called “The World of Art with Alfred Morang.” Most of all he was famous for his enthusiasm for art and his ability to teach and many benefited from “The Morang School of Fine Art”.

Walt Wiggins authored a book published in 1979 appropriately titled “Alfred Morang…A Neglected Master”. Walt uncovered several quotes during his research for his book and my favorites include the following. “When Alfred Morang’s life came to a tragic end in January of 1958 nothing before or since has so shaken the New Mexico art colony. Some say it was a sense of guilt that struck the community for not having shown a greater sense of appreciation for one who, by destiny, was different.” One Santa Fe artist reasoned, “Why shouldn’t Santa Fe be stunned with the loss of Alfred? After all, he taught half of us how to paint and the other half how to see.”

The February 10th 1958 issue of the Santa Fe New Mexican carried the report of the local memorial service for Alfred in Lorraine Carr’s column “It Happened in Old Santa Fe”. Dr. Reginald Fisher, director of the Art Museum spoke first. “Friends this is not a funeral, we are simply gathered here for a creative expression of merit and appreciation of a spirit that has been active in an activity that we in Santa Fe like to call art. Alfred was an inventive, searching and daring spirit as French as Lautrec, yet he never saw Paris. Last week his restless spirit found peace.”

Painter and close friend Randall Davey was next. “I have known Alfred since he arrived back in 1937. He was a kind, a gentle and a humble soul and in all those years I never heard him speak unkindly of his fellow man. He was a great painter; many of you did not think so, because often he sold his work for a mere pittance through necessity. Nevertheless it was great art and the happiest work I have seen in New Mexico. He had a love and a delight for painting and I doubt that anyone will surpass him in this field.”

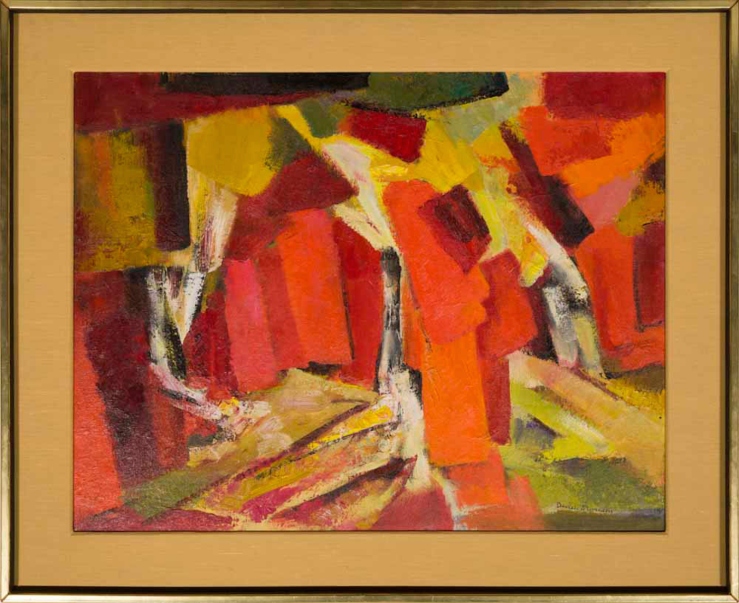

Alfred Morang, Untitled (Mountain Landscape), Oil on Board

Alfred Morang, Untitled (Mountain Landscape), Oil on Board

I hope Alfred enjoyed himself on that Tuesday. I hope he spent some time with friends and some extra time petting his cats. I hope he wrote another poem and put the final touches on his most recent favorite painting before he headed down the alley to Claude’s that evening.

Claude James ran the well-known Canyon Road bar where he often spent time and, as legend has it, her rowdy spirit was just what was needed to run that place. I would love to have met Alfred there that fateful night for a few drinks. I’m sure we would have talked through the evening about art and life as we cast occasional glances at the ever present ladies that were often the subject of his paintings and when Claude said “It’s midnight, would you fellows like another one?” I would nod and say, how about a couple of shots of your best cognac. I would love to take a sip, lean back and turn to him and say “Alfred I know you often say that you don’t believe in art for art’s sake, but you believe in art for people’s sake. Can you explain to me what you mean by that, and please…take your time?”

A few weeks after I finished writing this story I found myself engrossed in the details of planning a trip to Paris. I was not sure why, but suddenly it came flooding over me with incredible clarity. Human life really is very fragile and it really is all going to come to an end someday and we do not know when. I knew then I needed to go to Paris and I needed to go now. Unfortunately most people have that epiphany too late in life. They start thinking about the things they never got to do after it’s too late to do them. I knew then that this sudden obsession with Paris was a message from Alfred. Paris was his promised land, but he never made it there and I was going to go for both of us.

I told a friend in Santa Fe this story and he said, “You should do something for Alfred in Paris.” It was a great idea, but what would I do? I had been in Paris 5 days when I suddenly knew. I found an image of a Morang painting on my laptop. I printed it and wrote a bit on the back about Alfred and headed off to the Musee d’Orsay. This time as I enjoyed the paintings I was also searching for a repository for Alfred’s work and I finally found it. I can tell you that a fine example of the genius of Alfred Morang now has a home in Musee d’Orsay on the banks of the Seine and it will take a jackhammer to find it. He is close to Monet and Bonnard, the masters he so admired. Alfred, you finally made it.

Source: Bill Tate’s tale first appeared in the 1979 book Alfred Morang: A Neglected Master by Walt Wiggins.