Roch Hart’s jeep outside Matthews Gallery

Roch Hart’s jeep outside Matthews Gallery

Roch Hart is the first and only fine furniture maker in our stable, but he also has a pretty awesome day job. As the owner of New Mexico Jeep Tours, Hart takes visitors on rugged expeditions across a 20,000 acre private ranch between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. The property is home to wild horses and numerous petroglyphs left behind by ancient Pueblo cultures.

We first met Hart through the image sharing website Flickr, where he posts stunning photographs from his adventures. We had no idea that he was also a master craftsman until he reached out to us. Not long after, a big red jeep full of beautiful hand-carved benches appeared outside the gallery. When we saw how good Hart’s work looked in our Southwestern art room, we knew it was a perfect match.

It didn’t take long to realize that Hart’s adventurous occupation and his impressive hobby were connected. As chronicled in previous posts, many of his works feature symbols from the petroglyphs he discovers on the ranch. The ancient marks are part of a complex language, and their meanings are partly lost to history. Luckily, Hart is a passionate detective. We asked him to show us some of his photos and tell the stories of petroglyphs that have inspired his work.

Take it away, Roch:

New Mexico state flag, and a cross from Roch’s pie chest ‘The Way‘

In petroglyphs, the same symbol can hold multiple meanings. Take for example the Zia symbol on our state flag. Our European or Western paradigms might lead us to interpret the Zia as a simple, decorative depiction of the sun, but in the Pueblo culture these symbols were a communication form rather than an art form. The circle of the Zia represents the circle of life. The four rays radiating from the circle represent many different things: the four directions, the seasons, the elements or even four stages in a person’s life. In the Pueblo culture, the four is a sacred number. I have found petroglyphs with faces whose mouths are in a square shape, perhaps speaking of the fours.

Roch Hart with New Mexico petroglyphs, a similar design on Hart’s pie safe ‘The Way‘

Sometimes petroglyphs mimic the lines and rhythms of nature. I’ve been told by a trusted, unnamed native source that the triangular petroglyphs in the photo above represent mountains. The straight lines below the mountains may represent mesas, and below that is a mark that resembles a body of water. This could be a map of sorts. Not far from this petroglyph, there is a small pond with a view of mesas and the Jemez Mountains. On my latest pie safe, ‘The Way‘, I carved a similar pattern to represent mountains.

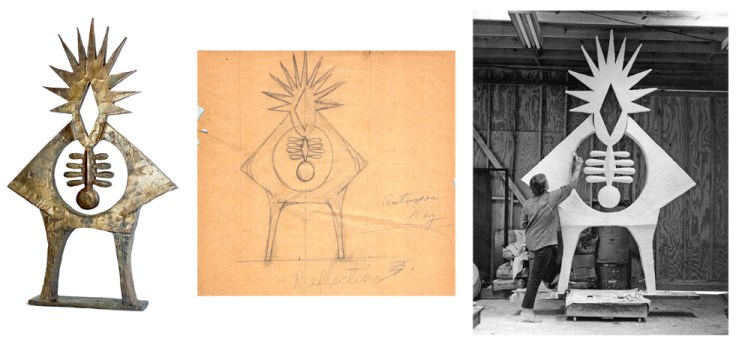

Shield Warrior petroglyph, photo by Roch Hart

Shield Warrior petroglyph, photo by Roch Hart

In the world of petroglyphs there is a common theme of anthropomorphism (I really just like saying that word). Humans will sometimes take on the form of an animal, insect, or warrior shield. In the simple petroglyph above, a circled cross with a head and eyes represents a Shield Warrior. If we were still doing petroglyphs, this one could have represented me during my days as a cop. As you can see, this little guy also has the cross in his shield, representing the fours or ‘the way.’

Bear claw petroglyphs with storyteller and listener faces, photo by Roch Hart

Bear claw petroglyphs with storyteller and listener faces, photo by Roch Hart

Another common theme in petroglyphs is the ‘yin and yang.’ For instance, every storyteller needs a listener. The images above show petroglyphs that represent bear tracks. The tracks come in pairs, and each track has a face inside it representing a storyteller or a listener.

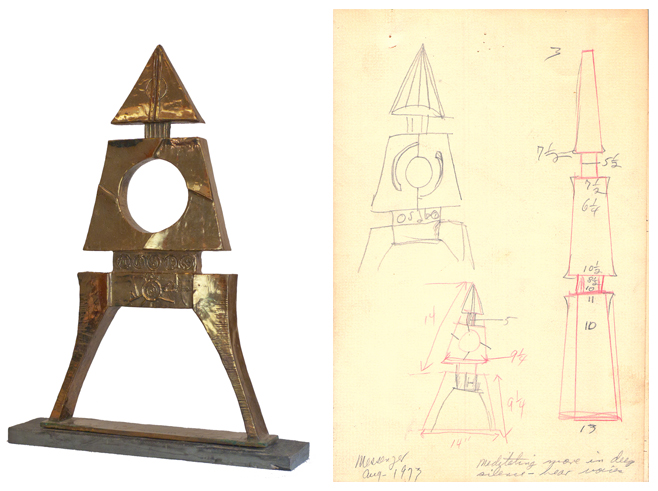

‘Marriage’ petroglyph, faces on Hart’s pie safe ‘The Storytellers‘

I call the petroglyph above ‘The Marriage.’ You can see two distinct people occupying one checkerboard body. If you look carefully, the square head appears to be speaking while the round head has its mouth closed. My pie safe called ‘The Storytellers‘ explores this theme of opposites. The listener and the speaker depend on each other.

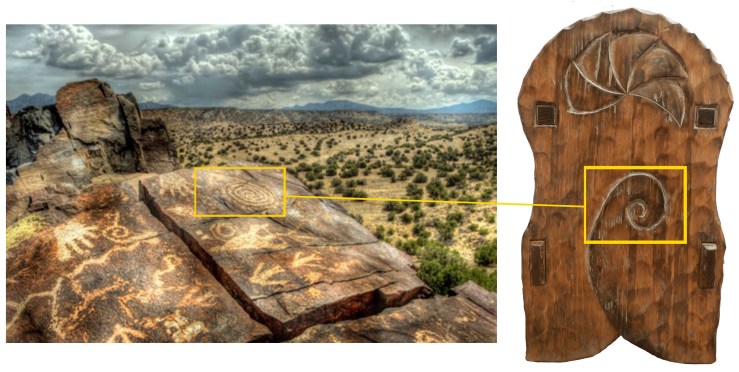

New Mexico petroglyphs, a spiral design on a bench by Roch Hart

Another common symbol is the spiral. Spirals or concentric circles often represent time or travel. I have found that cracks are often incorporated into these petroglyphs and I will find a spiral with the outer end going to or ending in a crack. A common legend amongst the Pueblo natives is that they originated under the earth’s crust and made the journey to surface. I believe these spirals convey that journey. On one of my early pie safes, I placed a spiral on the door with the tail leading up to the middle joint of the door.

Petroglyphs are very complex and have multiple layers of meaning and legend. This blog post just scratches the surface, so to speak. We have lost much knowledge of petroglyphs because early Spanish priests saw them as spiritualism apart from Catholicism. Catholicism was the state religion and the only legal one, so petroglyphs were outlawed. In fact we often find crucifixes etched into the stones near these sites, placed there by the early priests to exorcise the place of evil spiritualism and to remind the Pueblo natives that this was not longer an accepted practice.

While part of me is upset about how we lost the knowledge of these ancient symbols, I enjoy that I don’t completely understand the mystery. I love the idea that in some respects it is open to the interpretation of the beholder. Only the maker knew.

To make my fine furniture, I blend influence from the native cultures with my knowledge of Spanish colonial carpentry laws. That’s how I arrive on how to make a piece down to the joinery. But that’s for another blog post!

To see more photos by Hart, make sure to check out his Flickr account. See all of his furniture on our website, and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest for daily gallery news.