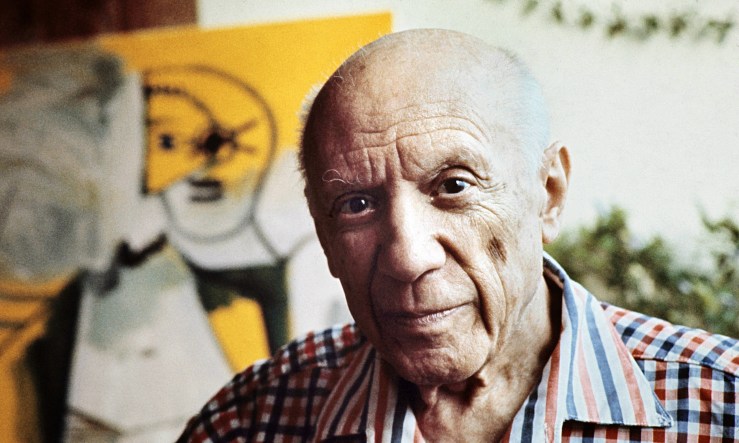

Picasso and his sister Lola. He was about 8 years old

Picasso and his sister Lola. He was about 8 years old

in this picture, and already had some swagger.

In the art world, it’s a holiday. Pablo Picasso was born in Málaga, Spain on October 25, 1881. In the 133 years since, the artist has irrevocably changed the way we look at art— and the world around it.

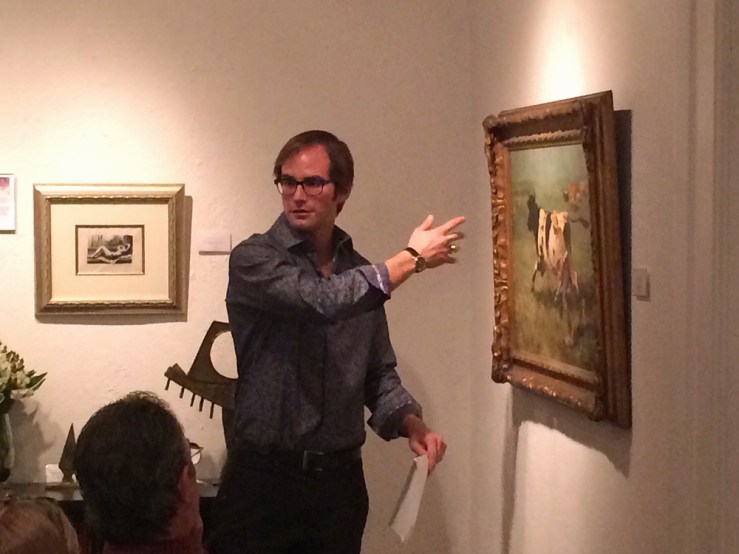

We’re frequently struck by the way Picasso would capture an artist’s attention and radically alter his or her course. Just look at this 1955 lithograph by Italian futurist Gino Severini, which is often mistaken for a Picasso by gallery visitors. French artist Jean-Pierre Jouffroy shifted from figurative artwork to pure abstraction after studying Picasso and his contemporaries, and Robert Motherwell‘s decision to become an artist hinged on a European tour of modern masterworks.

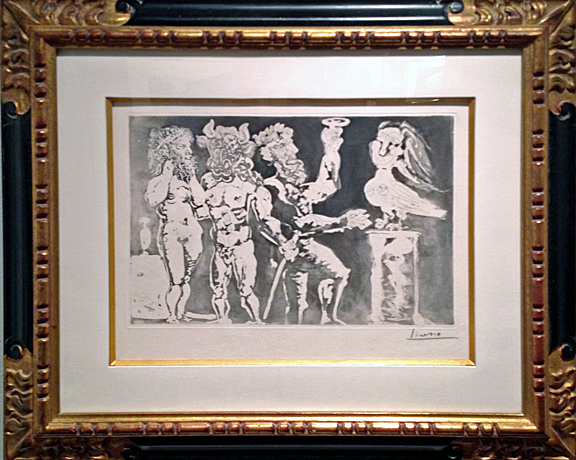

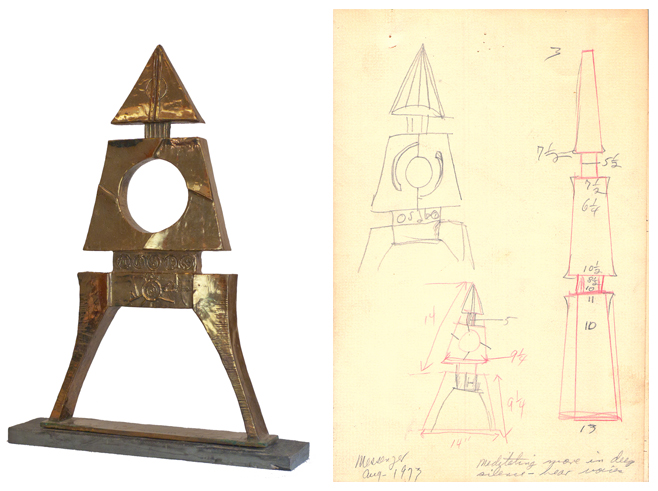

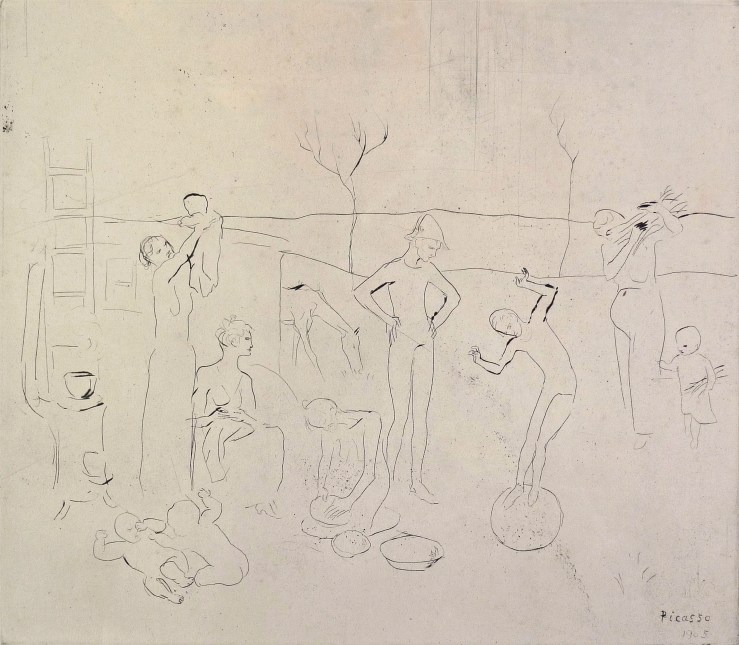

On this momentous day, we’re looking back at every Picasso that has passed through our gallery. Each one has a fascinating story…  Les Saltimbanques is the earliest work by Picasso we’ve ever exhibited. It’s a drypoint from 1905, when the artist was about 24. It was commissioned by legendary art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who gave Picasso his first gallery show in 1901. The frolicking figures are characters from an opera-comique about a circus troupe. An early appearance by the harlequin (far right) is notable, as the archetype would become one of Picasso’s most-used personal symbols.

Les Saltimbanques is the earliest work by Picasso we’ve ever exhibited. It’s a drypoint from 1905, when the artist was about 24. It was commissioned by legendary art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who gave Picasso his first gallery show in 1901. The frolicking figures are characters from an opera-comique about a circus troupe. An early appearance by the harlequin (far right) is notable, as the archetype would become one of Picasso’s most-used personal symbols.

Fast forward to 1930. With the help of Vollard, Picasso had built his name into the first true global artistic brand. In yet another stroke of marketing genius, Vollard commissioned Picasso to create a series of 100 etchings—including several portraits of the dealer himself. The star of the Vollard Suite is the minotaur (second from left), another one of Picasso’s personal symbols. At the beginning of the series the minotaur is a virile beast, but by the end he is blind and weak, relying on a beautiful young muse to guide him. Completed in 1937, it’s the middle-aged Picasso’s meditation on his waning virility.

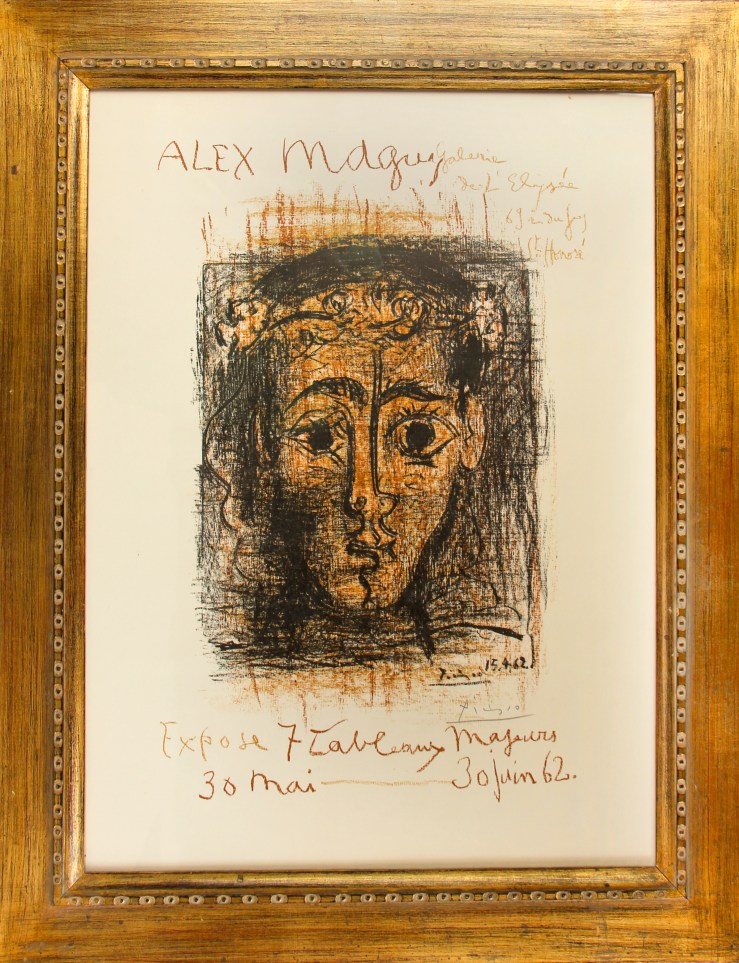

A youthful face peers from this offset lithograph Picasso designed for the Alex Maguy gallery in 1962. The exhibition was a retrospective of his artwork, but those captivating, wonder-filled eyes hardly hint at the darker themes the octogenarian turned to in his later years.

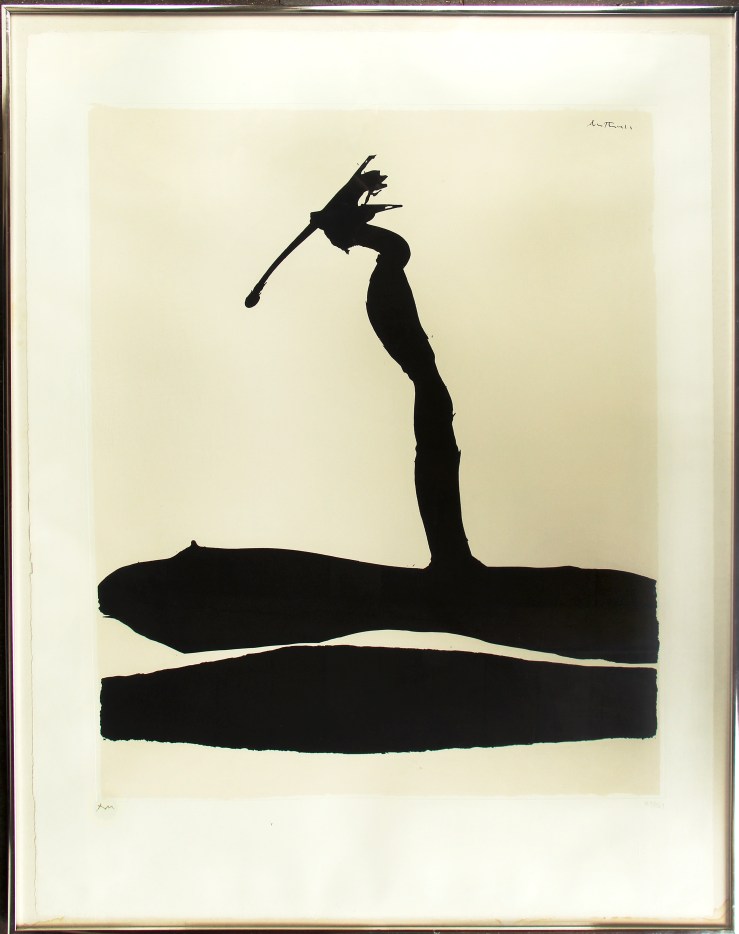

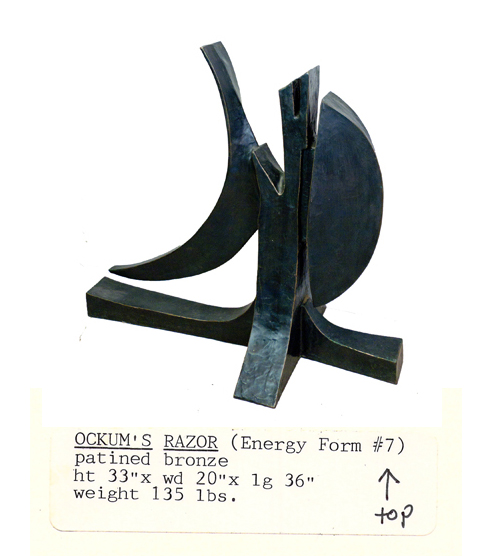

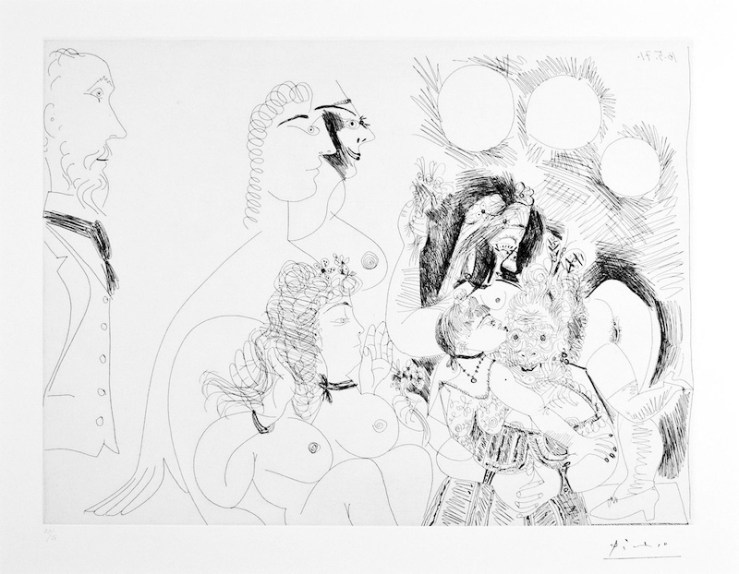

Picasso created the 156 Suite in 1971, not long before his death. Some consider the etchings to be his most personal series, a diary of a man struggling with impotence and pushing helplessly against the inevitable.

Picasso created the 156 Suite in 1971, not long before his death. Some consider the etchings to be his most personal series, a diary of a man struggling with impotence and pushing helplessly against the inevitable.

In contrast to our print from the Vollard Suite, women take the dominant role in these works. Models turn on artists, witch doctors stab at their patients and—in the case of this print—prostitutes tangle at a brothel while a man looks on, paralyzed. The gentleman is Degas, who appears in several prints in the series and with whom Picasso felt solidarity in his struggles.

Check out our Twitter, Tumblr and Pinterest profiles today for more insight on Picasso, and learn more about all of the artwork in this post on our homepage.

Check out our Twitter, Tumblr and Pinterest profiles today for more insight on Picasso, and learn more about all of the artwork in this post on our homepage.