Boxer (left) and Motherwell

Boxer (left) and Motherwell

It was Mark Rothko’s 111th birthday this Friday, and the occasion has us pondering one of the 20th century’s most polarizing art movements: abstract expressionism.

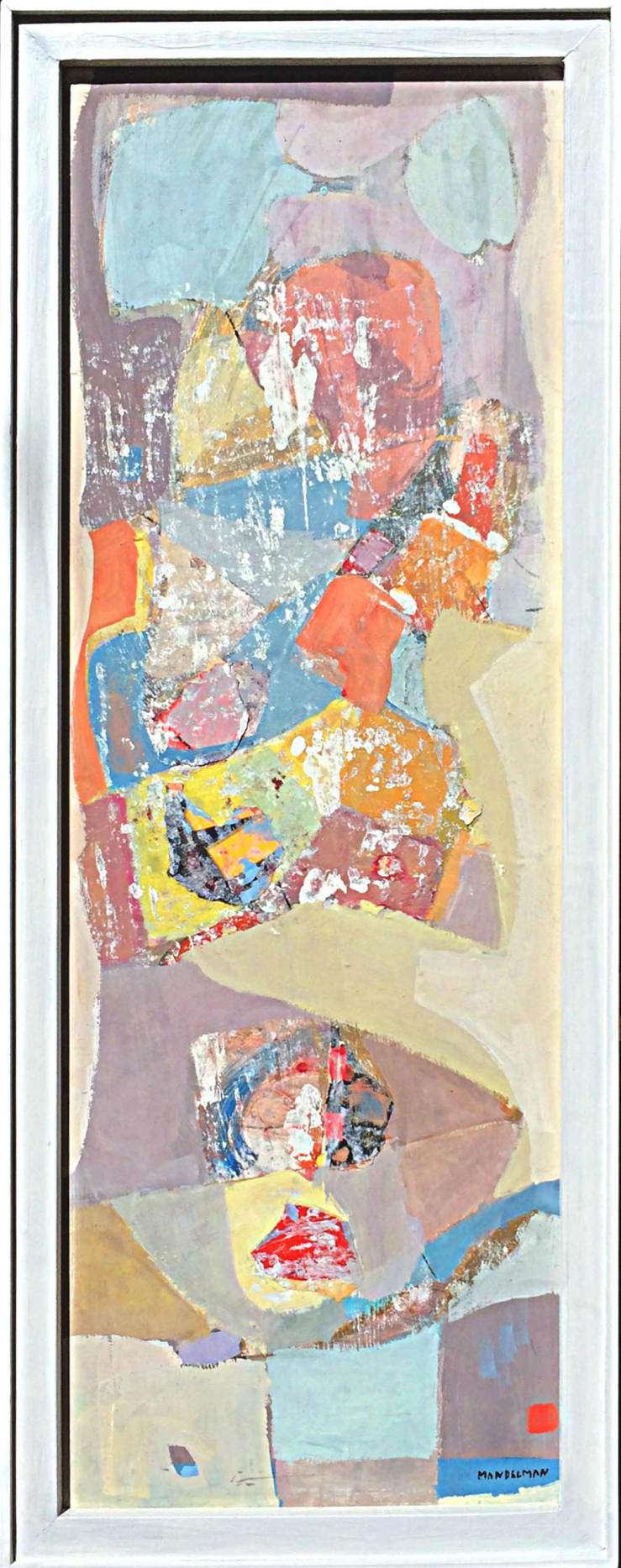

Three artworks by renowned abstract expressionists have recently landed on our walls. The first two are heavily impastoed oil paintings by Stanley Boxer, who resolutely clung to the far fringes of the movement. Determined to defy labels, he was furious when art critic Clement Greenberg called him a color field painter, and yet the arc of his creative explorations closely paralleled that of his abstract expressionist contemporaries:

In the manufacture of my art, I use anything and everything which gets the job done without any sentiment or sanctity as to medium. Then, too, I have deliberately made a practice of being “visionless”… this is, I go where my preceding art takes me, and never try to redirect the future as to what my art should look like. This is a general credo and foundation for everything I have ever done and stands firm in its solidity as this is written.

Boxer, who died in 2000, would have loved Grace Glueck’s New York Times review of a 2004 exhibition of his late works. She notes that he was “never part of a movement or trend,” but rather driven by paint’s “physical possibilities without script or program.”

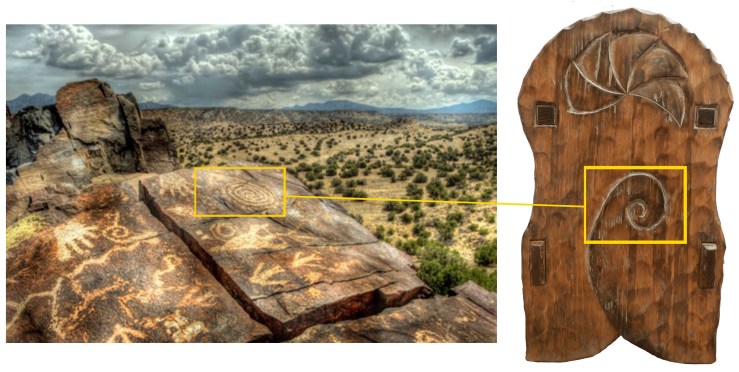

Atriumofashreddednight (top) and Crisppitchofsigh, Oil on Linen

Atriumofashreddednight (top) and Crisppitchofsigh, Oil on Linen

Glueck ends the piece with a brief analysis of Boxer’s titles, lyrical lists of words that are jammed together in unbroken strings. The works in our collection, for example, have names that read like fragments of beat poems: Atriumofashreddednight and Crisppitchofsigh. Glueck writes, “As Boxer joked in his titles, these canvases, more than most, do not really lend themselves to verbal exposition. They live for the eye, to which they bring deep satisfaction.”

Boxer’s titles provide a link to Robert Motherwell, the other abstract expressionist represented in our collection. Unlike many “abex” artists who labeled their canvases using dates or arbitrary numbers, Boxer and Motherwell were unapologetic in their wordplay.

That’s where the similarity ends. While Boxer considered himself an isolated frontiersman of abstract painting, Motherwell was an eager icon of abstract expressionism. He coined the term ‘New York School’ to describe his revolutionary circle, which included Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, and acted as a spokesperson for the movement in the world of academia.

If Boxer’s titles were little more than impressionistic quips, Motherwell, who was a scholar before he became a “serious artist” and wrote numerous essays on aesthetics, chose names that have inspired endless analysis. His most famous series of paintings, Elegies to the Spanish Republic, chronicles the Spanish Civil War in bold strokes of black and white and subtle passages of ochre, blue, green and red.

“Mainly, I use each color as simply symbolic: ochre for the earth, green for the grass, blue for the sky and sea,” Motherwell wrote. “I guess that black and white, which I use most often, tend to be protagonists.” In varying contexts, each color holds a universe of meanings. To fully understand the use of ochre in Motherwell’s Spanish Elegies, “You would have to know that a Spanish bull ring is made of sand of an ochre color,” the artist wrote. Other works that feature ochre, like Western Air or Personage, with Yellow Ochre and White, would naturally spark different associations.

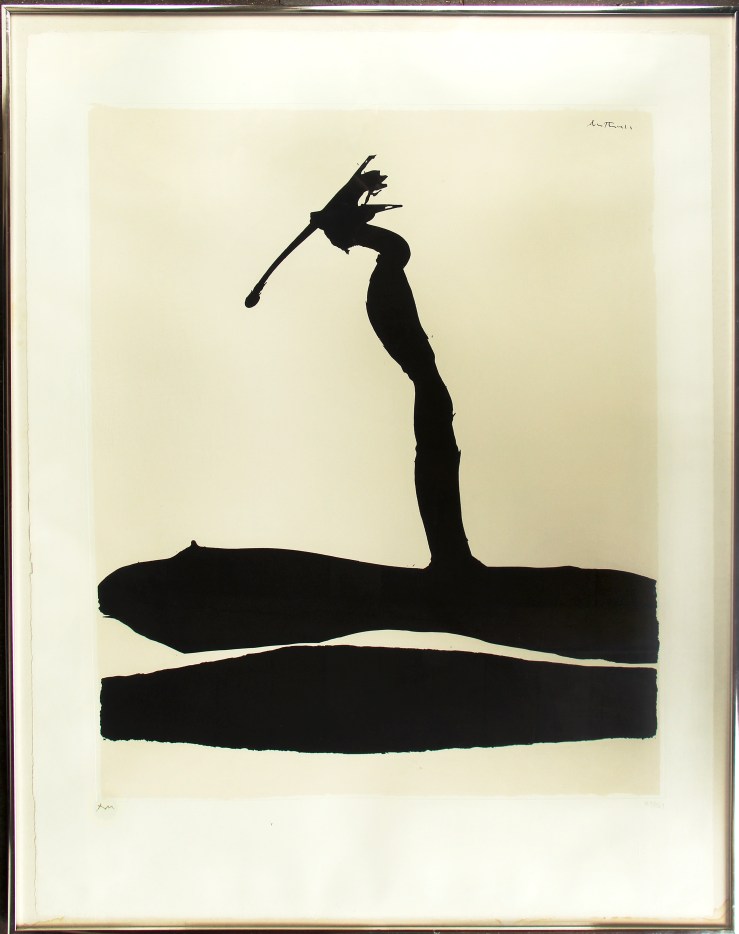

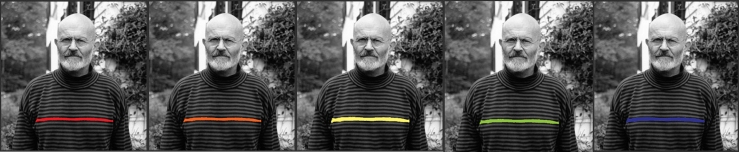

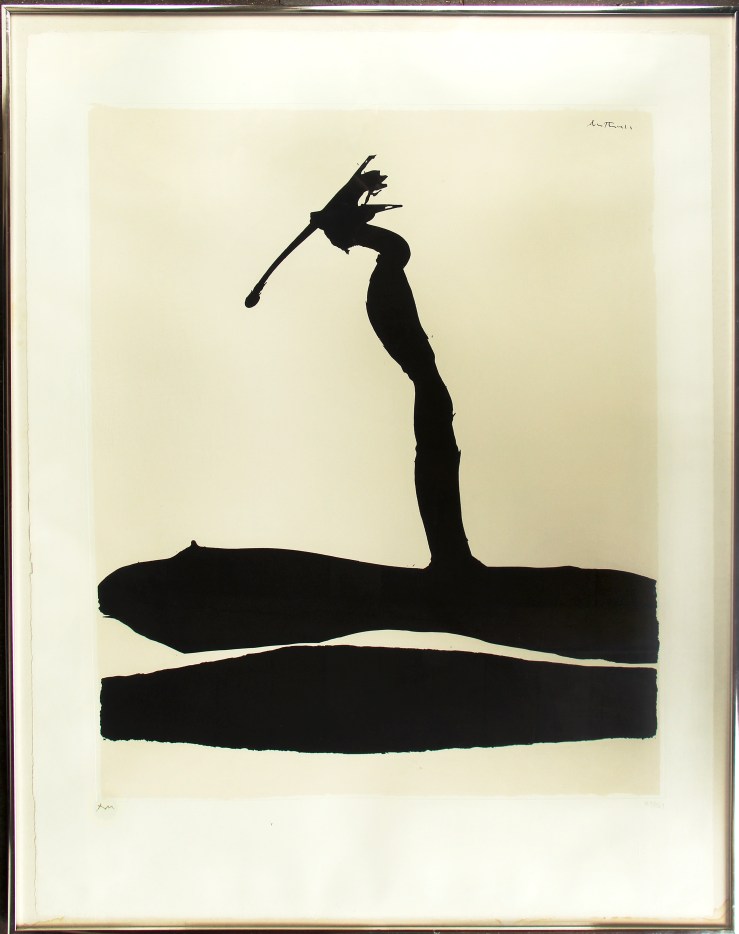

Robert Motherwell, Africa 4, Silkscreen

Robert Motherwell, Africa 4, Silkscreen

What to make of our Motherwell silkscreen, titled Africa 4? Motherwell completed the Africa suite in 1970, the same year he created his Basque and London suites. They were his first projects entirely devoted to silkscreens, and a divergence from the heavily layered nuances of his oil paintings. Here his black abstract forms stand crisply against their off-white backgrounds, although on closer inspection, their tumultuous edges still seem to weave in an out of focus.

“All my works [consist] of a dialectic between the conscious (straight lines, designed shapes, weighed color, abstract language) and the unconscious (soft lines, obscured shapes, automatism) resolved into a synthesis,” the artist wrote in 1944.

Motherwell first explored the concepts of automatism and the subconscious with a group of Parisian Surrealists, including Duchamp, Ernst and Masson, who had fled Europe during World War II. Their ideas would help shape the spiritual side of abstract expressionism, a spontaneous, intuitive element that Motherwell carefully balanced with his more intellectual inclinations.

Motherwell’s connection to the Surrealists lends us a potential clue to the significance of the ‘Africa’ title. In his 1946 essay ‘Beyond the Aesthetics‘, Motherwell discusses the life of French Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, who helped inspire Surrealism. In the final decades of his life Rimbaud quit writing and set off on an African expedition, a leap of faith that Motherwell compares to the Surrealists’ break from Dada and formation of a new movement:

Like Rimbaud before them, the Surrealists abandoned the aesthetic altogether; it takes a certain courage to leave poetry for Africa (as Rimbaud did, fh). They revealed their insight as essentially moral in never forgetting for a moment that most living is a process of conforming to an established order which is inhuman in its drives and consequences. Their hatred sustained them through all the humiliating situations in which the modern artist find himself, and led them to conceptions beyond the reach of more passive souls. For them true ‘poetry’ was freedom from mechanical social responses. No wonder they loved the work of children and the insane – if not the creatures themselves.

Perhaps Motherwell’s Africa suite represents a similar journey, a leap into the unknown that is a clear break from previous adventures. Just as Rimbaud abandoned an intellectual pursuit for one centered on travel and action, and as the Surrealists broke from the societal battles of the Dadaists to explore dreamscapes, so Motherwell’s stark Africa forms landed him in a new realm of image-making. Perhaps he sought to prove that even the most distinctly divided blacks and whites could possess endless shades of grey.

Learn more about Stanley Boxer and Robert Motherwell on our website, and make sure to connect with us on Facebook, Twitter and Flickr for more gallery news.

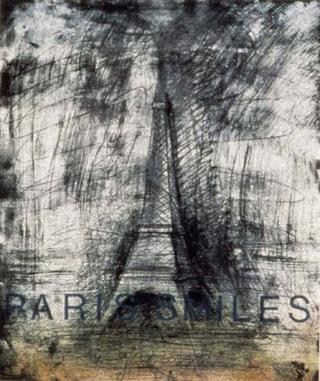

Picasso and his sister Lola. He was about 8 years old

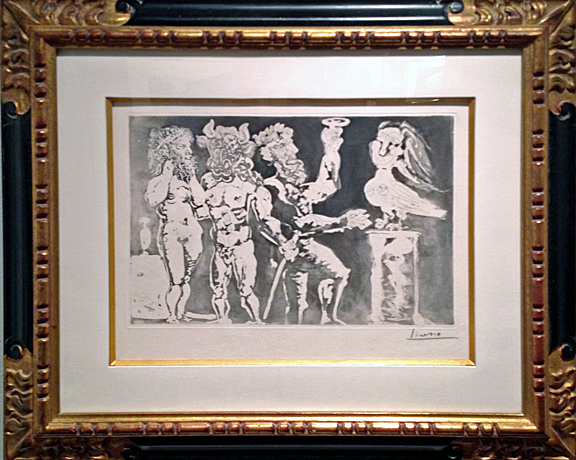

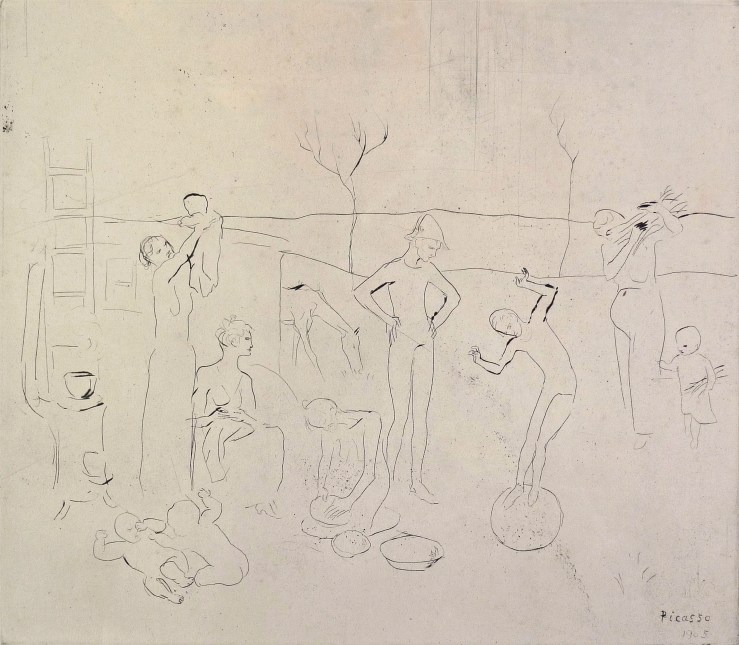

Picasso and his sister Lola. He was about 8 years old Les Saltimbanques is the earliest work by Picasso we’ve ever exhibited. It’s a drypoint from 1905, when the artist was about 24. It was commissioned by legendary art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who gave Picasso his first gallery show in 1901. The frolicking figures are characters from an opera-comique about a circus troupe. An early appearance by the harlequin (far right) is notable, as the archetype would become one of Picasso’s most-used personal symbols.

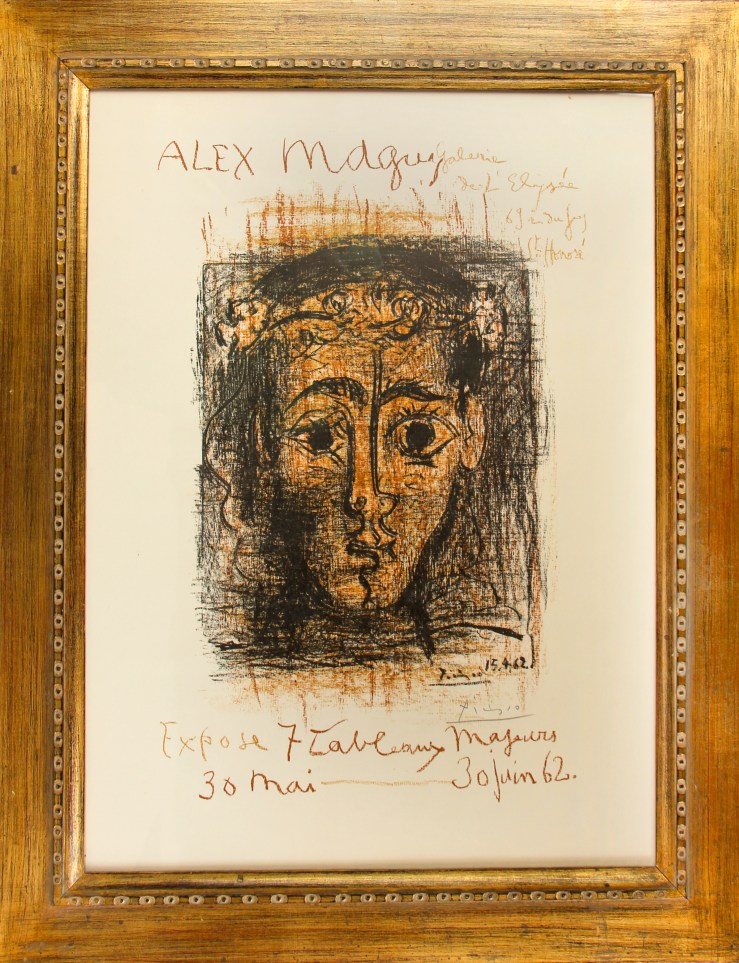

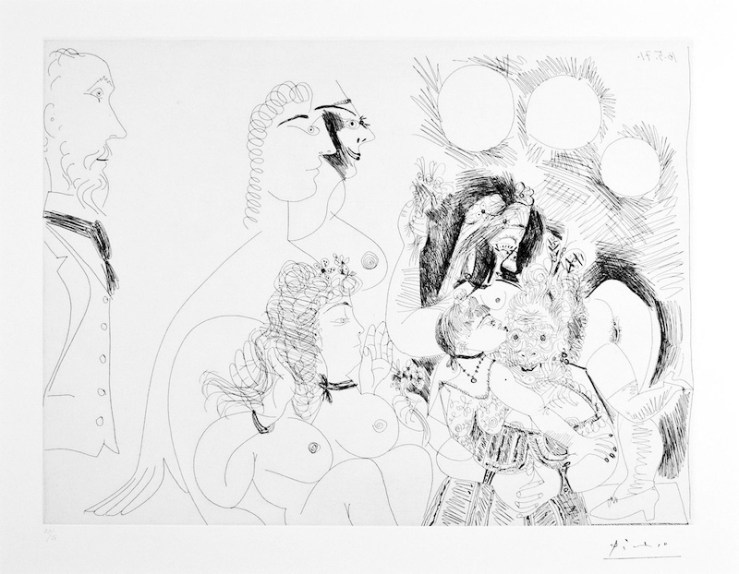

Les Saltimbanques is the earliest work by Picasso we’ve ever exhibited. It’s a drypoint from 1905, when the artist was about 24. It was commissioned by legendary art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who gave Picasso his first gallery show in 1901. The frolicking figures are characters from an opera-comique about a circus troupe. An early appearance by the harlequin (far right) is notable, as the archetype would become one of Picasso’s most-used personal symbols. Picasso created the 156 Suite in 1971, not long before his death. Some consider the etchings to be his most personal series, a diary of a man struggling with impotence and pushing helplessly against the inevitable.

Picasso created the 156 Suite in 1971, not long before his death. Some consider the etchings to be his most personal series, a diary of a man struggling with impotence and pushing helplessly against the inevitable. Check out our Twitter, Tumblr and Pinterest profiles today for more insight on Picasso, and learn more about all of the artwork in this post on our homepage.

Check out our Twitter, Tumblr and Pinterest profiles today for more insight on Picasso, and learn more about all of the artwork in this post on our homepage.