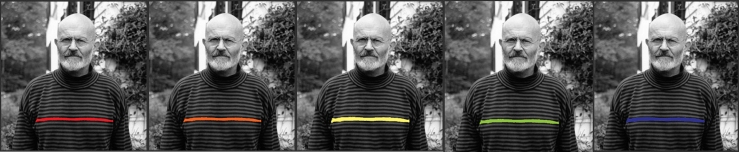

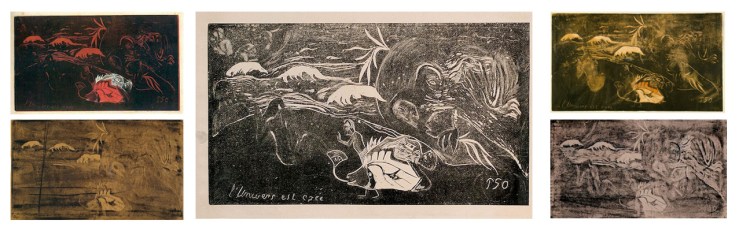

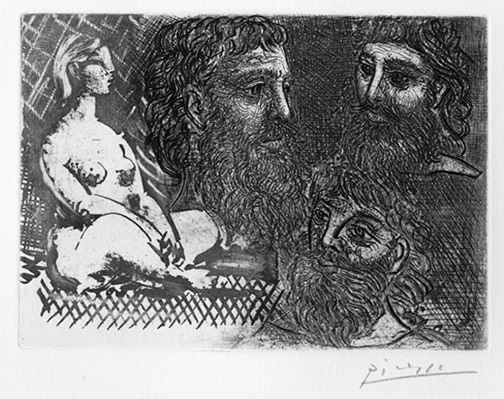

William Lumpkins Jr. next to his father’s serigraph “Abstract Landscape #3“

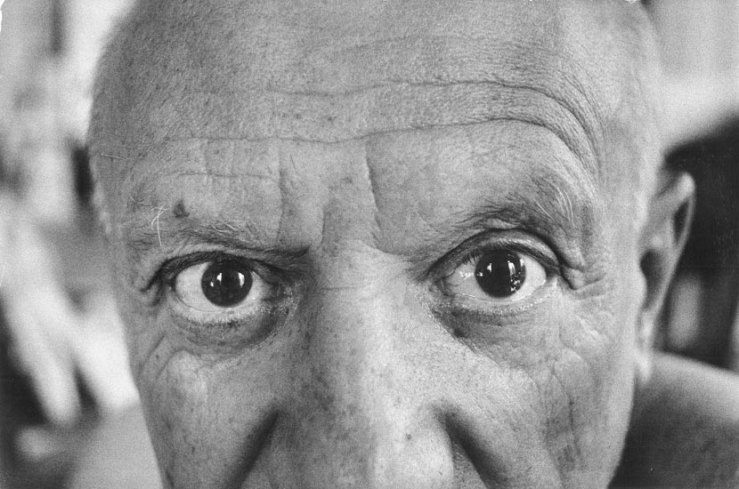

At last Friday’s opening of NEW MEXICO MODERNS: The Lumpkins Files, William Lumpkins Jr. was a quiet presence. He stood to the side surveying his father’s work or chatted softly with visitors, many of whom were family friends. One woman had known his dad, who died in 2000, through an art discussion group that met at local coffeehouses. “Whenever Bill spoke, we all had to lean in. He was such a lovely, gentle man,” she said.

Will’s father may have passed down his mild temperament, but both men are also legendary for their fierce artistic passion. Will has carefully preserved the artwork in The Lumpkins Files show for years, and meanwhile has developed his own artistic style. The jacket he wore to the show was emblazoned with intricate celtic knots and a dragonfly.

When we asked about his dad, the more colorful side of Will’s personality emerged. Here’s William Lumpkins’ son on his father’s never-before-seen artwork, and why he decided to release it more than 15 years after Lumpkins’ death.

What’s it like to see your dad’s work hanging in the gallery?

Well, his work was all around us growing up, so it’s not that strange. The gallery did an excellent job though.

When did you first bring the work to Matthews Gallery?

About a year and a half ago. I had shopped around and didn’t relate to anybody until I met Larry.

Where did you keep it for all these years?

I had it in a case between sheets of acid-free paper. When I was teaching at Virginia Commonwealth University, I was in charge of museology. It was a whole print and painting conservation training program. So my dad knew that I could take care of them. Watercolors in particular are a sensitive thing for archiving.

Why didn’t he want you to release them until now?

It didn’t have to do with the work. He said to me, ‘Okay, you wait until after you’re 70 because by then your personal artistic statement will be you. You won’t have to mimic me.’ So at 70, my artwork was me and I brought these out again.

Were you ever tempted to release them before that?

No, it just didn’t seem right until I started looking around recently. I trusted you guys.

One of the biggest surprises in this body of work was the watercolor from 1937. That’s one of the earliest Lumpkins pieces we’ve ever seen. Did you know it was in there?

I knew that the work spanned a lot of time. When Dad was closing down the studio, he picked these out because these were the ones that he really liked from different points in his career. He felt that they were significant, and that they weren’t typical. His typical work is pretty well-known, but these he wanted to hold out so that they’d be totally new.

What was your vision for this show?

I gave the work to Larry and said, ‘Do you what you think is best.’ I just want them to be out in the open where they can be seen. If people want them enough, if people like them a lot, that’s good.

Hear more from Will Lumpkins in this week’s Pasatiempo, and visit the show at Matthews Gallery through Friday, April 25. For more images from the opening, check out our photos page and connect with us on Facebook and Instagram.